It’s been three years since the morning Greenwich residents woke up to discover the red and white Trump/Camillo lawn signs.

For a split second they blended into the sea of candidate signs that proliferated inside rotaries and along median strips 11 days before the Nov 5 municipal election pitting Republican Fred Camillo against Democrat Jill Oberlander for First Selectman.

The signs featured an elephant, the slogans “Local Elections Matter,” and “Make Greenwich Great Again,” as well as a website FredCamillo.com, which at the time directed to a militant pro-Trump website, Citizens for Trump.

In the moment it took for people to realize Trump and Camillo were not running on a slate together, some laughed. Others not so much.

The mystery of who was responsible for the signs gripped the town that weekend.

On Monday, October 28, when Greenwich Police Deputy Chief Mark Marino showed Captain Mark Kordick, a 31-year veteran of the police force, a copy of Kordick’s invoice for the signs, Kordick admitted he was responsible.

He was placed on paid leave by the Police Dept the same day.

On November 5, 2019, Camillo defeated Ms Oberlander.

Five months later, in April 2020, Kordick, who was still on leave, was terminated by Police Chief Heavey. The decision was announced by Camillo, who as First Selectman also serves as police commissioner, to whom the police chief reports.

A lawsuit was filed on Jun 30, 2020 by Kordick against the Town of Greenwich, Camillo, his campaign manager Richard Kriskey, First Selectman Peter Tesei who was in office during the sign incident, and Rich DiPreta who was the Republican Town Committee chair at the time.

Kordick claims there was retaliation against him for exercising his constitutionally protected right to engage in off duty political speech during an election. He also claims against individual defendants Camillo, Tesei, Kriskey and DiPreta for Tortious Interference with a contract, and Invasion of Privacy by learning his identity as purchaser of signs through the fraudulent means via agents of the campaign.

Since the incident occurred while Tesei was still First Selectman, his legal fees are covered by the Town of Greenwich. Camillo’s are not. Nor are Mr. Kriskey’s. Mr. DiPreta, an attorney, is represented by his wife, also an attorney.

Kordick vs the Town of Greenwich has wended its way through court for 2-1/2 years.

State of Connecticut Judicial Branch website is home to dozens of motions and hundreds of pages of transcripts of depositions and exhibits including text exchanges, campaign receipts and emails that were turned over during discovery. All are publicly available on the DOJ website here, with the most recent activity at the bottom of the page.

Little has been written about the court case until recently, when New York Times reporter and columnist Dan Barry traced the impact of Donald Trump on Greenwich Republicans (In Affluent Greenwich, It’s Republicans vs. ‘Trumplicans’ Nov 7, 2022).

Nov 29 Memorandum of Decision

Last Tuesday Judge Edward Krumeich issued a Memorandum of Decision concerning Kordick v Town of Greenwich. In a 35 page document, the judge denies the motions from the Town, Kriskey and Camillo for summary judgement to dismiss claims against them.

Judge Krumeich cites establish standards for deciding a motion for summary judgement, specifically that the trial court must view the evidence in the light most favorable to the nonmoving party.

“There are genuine issues of material fact that preclude summary judgement in favor of the Town, Camillo and Kriskey,” Krumeich writes.

He adds that the tortious interference claims against DiPreta and Tesei must be dismissed.

He notes that in his official capacity as First Selectman, Mr. Tesei was entitled to governmental immunity, and Mr. DiPreta, in his role as RTC chair, was separate from Camillo’s campaign.

Also, he said the Invasion of Privacy claim against DiPreta must be dismissed.

Further, Krumeich writes, “Neither was involved in the scheme to discover Kordick’s identity by fraudulent means.”

As of Dec 2, the case of Kordick vs Town of Greenwich is headed to trial in February.

Krumeich notes that before the Camillo campaign discovered Kordick’s involvement in the signs, Camillo, Kriskey and DiPreta had been concerned about the “fake” signs which they regarded as a political dirty trick, and wanted removed. They sought permission to remove the signs because of concerns that unauthorized removal of another’s campaign signs without authority would be illegal.

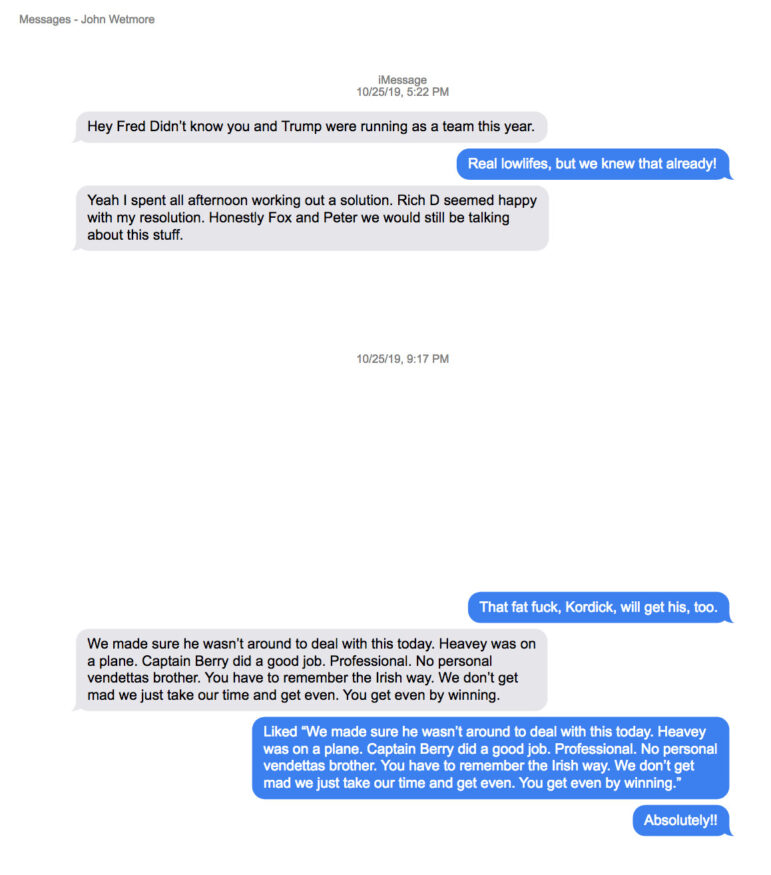

Tesei responded in a text to Kriskey, ‘Town cannot touch political signs unless for mowing or site line issues.’

On Oct 25, Police Captain Robert Berry sent an email to officers saying, “We will not be getting involved in managing sign content or the removal of alleged fake signs. Obviously this is a politically charged issue, and it is critical that as sworn police officers we remain neutral in political matters…”

But by the end of the day, Greenwich Police reversed the decision about whether the signs could be removed after a group teleconference with Tesei, DiPreta, Kriskey, the Greenwich Town Attorney, and Berry, though Krumeich notes on page 5 of his memorandum there were conflicting versions about who attended and what was discussed at the teleconference.

The RTC removed the signs over the weekend.

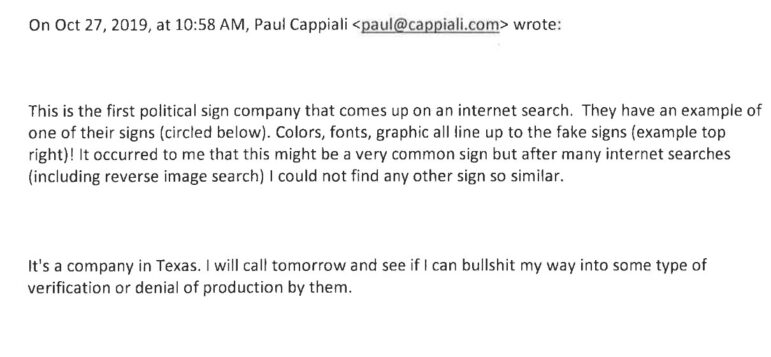

Krumeich’s memorandum says the Camillo campaign had been determined to identify who printed and posted the signs.

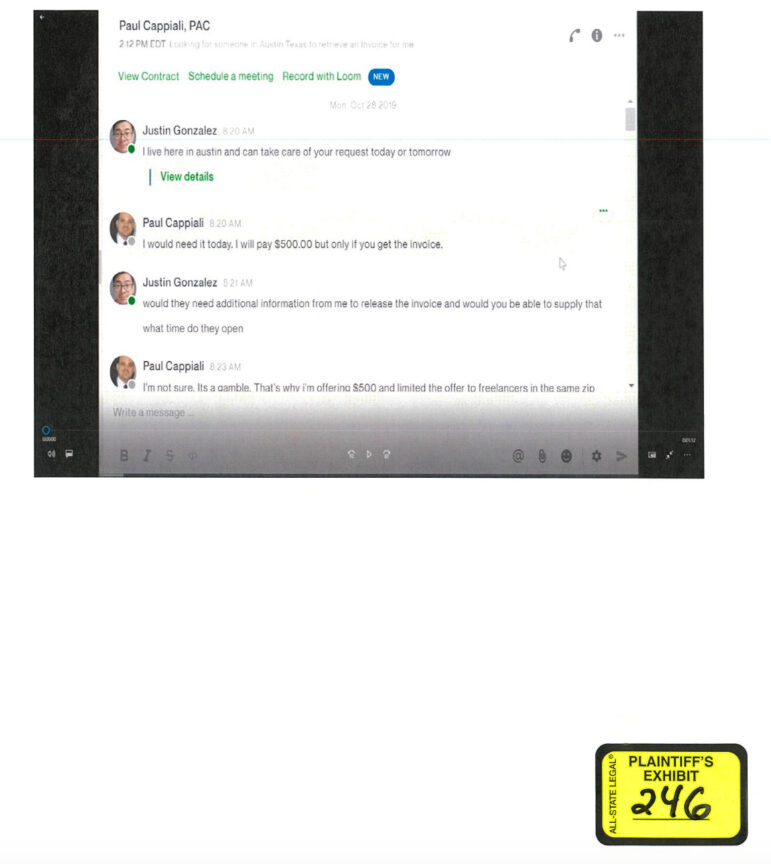

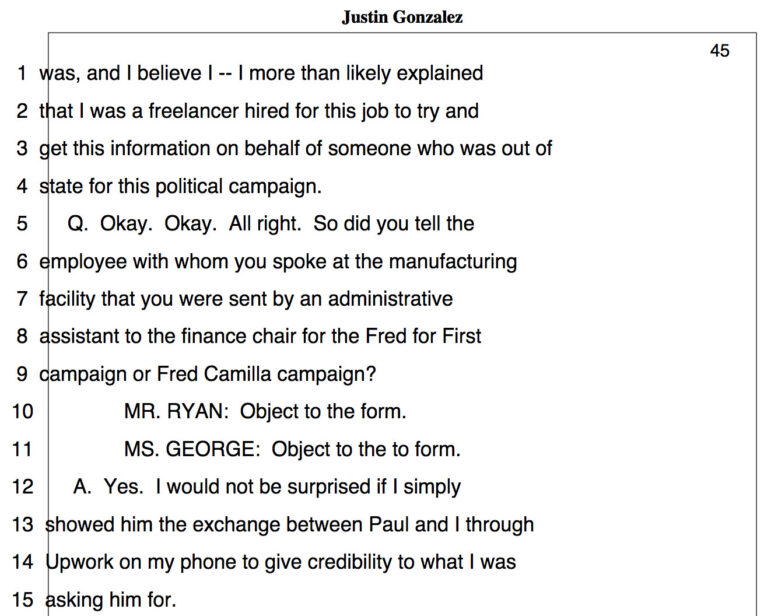

“On Monday, October 28, hired Camillo campaign workers had tracked the signs to a printing company in Texas and by using a ruse to pretend they represented the customer who printed the signs and by falsely representing they needed a copy of an invoice for their records and state filings they obtained the invoice that identified Kordick as the person responsible for the signs,” Krumeich writes in the memorandum.

In footnote 7 on page 6, Judge Krumeich writes:

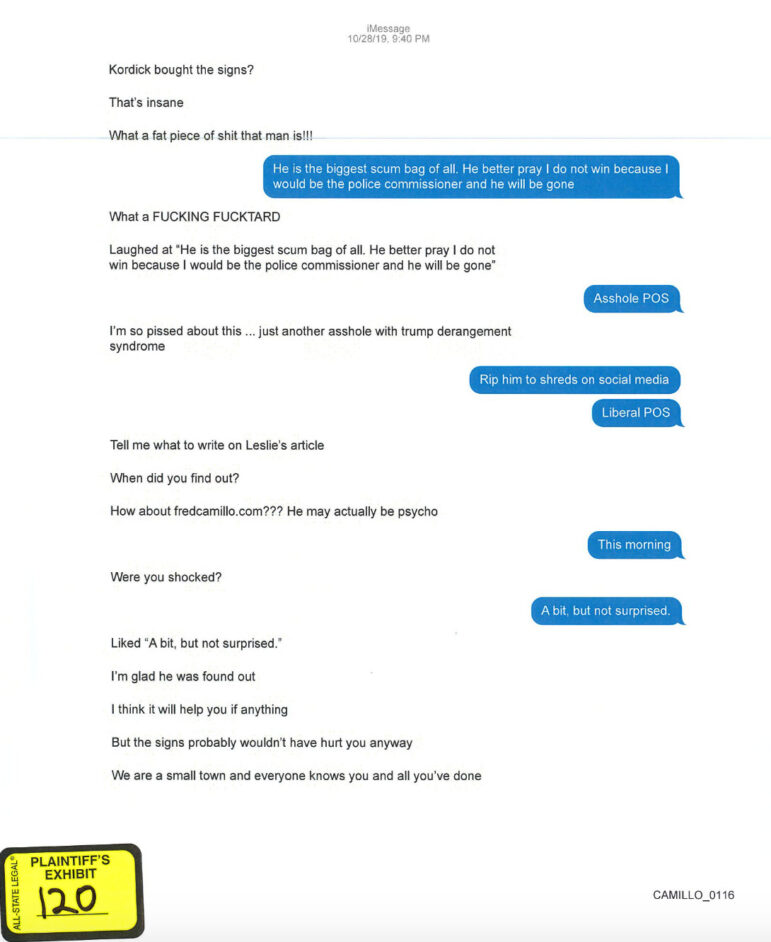

“Camillo’s reaction to the new information that Kordick bought the signs is reflected in his text message to a campaign worker that same day which read, ‘He is the biggest scum bag of all. He better pray I do not win because I would be police commissioner and he will be gone.’ The text also castigated Kordick for his liberal politics. Camillo’s dislike of Kordick preceded the discovery that Kordick was responsible for the Trump/Camillo signs.”

Krumeich continues: “In an email to John Wetmore of the Town Law Dept on October 25, before he knew the identity of the signs’ purchaser, Camillo stated: ‘That fat fuck Kordick, he’ll get his too.'”

After Kordick admitted his responsibility for the signs to Deputy Chief Marino, who was temporarily in command while Chief Heavey away, Mr. Tesei issued a press release to that effect.

From Oct 29 to Nov 4 there was extensive press coverage of Kordick’s suspension.

On Nov 5 Camillo was elected. He took office on Dec 1.

Krumeich notes that Camillo was not yet elected when Kordick was suspended, but he was First Selectman, also serving as Police Commissioner, when Kordick was investigated by internal affairs and later terminated on April 13, 2020.

During Kordick’s suspension, attorney Eric Daigle did an internal affairs investigation into whether the signs and web domain might violate the police department’s Unified Policy Manual, (UPM).

Krumeich writes about the internal affairs investigations and how a reasonable jury might view them. He says in a footnote: “There is some evidence that the Town Attorney and outside attorney Eric Daigle, who later conducted the internal affairs investigation about the signs, were consulted about what to do with Kordick because there were concerns about Kordick’s exercise of free speech rights.”

Krumeich writes in footnote 10 on page 7, “Berry also prepared a report entitled, ‘Fake Political Signs Investigation,’ considered by Daigle, that was highly critical of Kordick, which a jury could find to be erroneous and biased.”

Krumeich also notes that when Heavey terminated Kordick by letter on April 13, 2020, he outlined reasons, “including the UPM violations found by Daigle in connection with the signs and another investigation of a separate matter involving a dispute with another member of the Town’s Retirement Board.”

Krumeich writes in a footnote on page 8 that an initial investigation had already been conducted by Frank Ruderwicz of Blum Shapiro & Co into the incident on the Retirement Board on Sept 26, 2019 involving Kordick and Joe Pellegrino on behalf of the town attorney on a complaint from Kordick and a counter complaint by Pellegrino.

“The upshot of that investigation was that Pellegrino was in the wrong for using intemperate language and the counter-complaint was not upheld,” Krumeich writes in footnote 12 on page 8.

Krumeich notes on page 8 that the second investigation concluded there were UPM violations from both incidents.

First Amendment Rights, CGS 31-51q. “The Fourth Element” Page 8

Kordick accuses the town of violating his first amendment rights.

The Town argued that this claim must be dismissed because Kordick failed to prove “the fourth element” under Connecticut General Statute 31-51q, that ‘the exercise of his First Amendment rights did not substantially or materially interfere with his bona fide job performance or with his working relationship with his employer.’

The Town argued that Kordick admitted in his deposition that his involvement with the signs would interfere with his job performance and relationship with his employer when he explained why he posted the signs anonymously. Kordick countered by presenting evidence of good job performance in his 31-year career at GPD in which he rose to senior Captain, the third-highest ranking officer in the department, and a favorable review just three months before the sign incident.

Krumeich writes there is no evidence of changed circumstances other than the internal suspension, investigations and discipline which, “could be regarded by a reasonable jury as an exaggerated response to an isolated incident or pretextual.”

In a footnote on page 11, Kreumich writes, “Personal ill will between an employer and employee related to the exercise of free speech would not suffice to preclude satisfaction of the fourth element of Section 31-51q (4) or else the protections afforded by the Act would prove purely subjective and illusory.”

Krumeich writes that a reasonable jury could conclude that Camillo and Kriskey pushed for Kordick’s termination in their communications with Heavey and Berry in the time leading up to his suspension.

As for the fourth element Judge Krumeich said the jury could consider that the speech took place outside the workplace during his free time during a political campaign where free speech protections are at their highest.

Krumeich writes that there was no actual experience of any interference with Kordick’s job performance between the sign incident and his termination in April 2020 because he was suspended from Oct 28 until his termination.

Krumeich adds that, “The jury may also conclude that it was not ‘the exercise of his First Amendment rights’ that interfered with Kordick’s employment, but the political kerfuffle that occurred when the Camillo campaign surreptitiously uncovered and then outed Kordick’s identity to the Town, GPD and the public, and publicized his involvement in the Trump/Camillo signs and Camillo and Kriskey persuaded the GPD to take retaliatory action against Kordick.”

In footnote 21 on page 18, Krumeich writes that The Town rightly points out that anonymity of speech is not guaranteed and that even anonymous speech once publicly revealed may be grounds for dismissal in certain cases such as hate speech. But, Kreumeich writes, “The Town has not argued that linking Camillo with Trump sank to the level of hate speech.”

Krumeich writes that a jury may consider whether the reasons given for termination were pretextual and whether he was retaliated against for his political views.

He writes on page 19 there is evidence that Camillo bore personal malice toward Kordick and wanted him terminated and that, “A reasonable jury could conclude that Camillo and Kriskey communicated to Heavey and Berry and others what Camillo said in private text communications, that Camillo wanted Kordick to be fired.”

Also, Krumeich writes on page 19 that “a reasonable jury could conclude that terminating Kordick after he had been suspended for six months was an extreme reaction to an isolated incident that occurred off-duty over a brief four-day period during the heat of an election campaign.”

On page 20 Krumeich writes, “In considering this element the jury may weigh the success Kordick enjoyed during his thirty-one year career at the GPD against what they may consider a momentary lapse of judgement that set off a brief pubic relations problem that died out over a short time when the election was over and no more political advantage could be gained by professed outrage over the Trump Camillo signs.”

First Amendment and the Right to Anonymity

Krumeich writes that although Kordick realized that had his identity been revealed it would affect his job, particularly if Camillo were elected, he took steps to remain anonymous to protect his career and insulate the GPD from adverse publicity.

“The right to anonymity in the exercise of free speech is protected by the First Amendment,” Krumeich writes on page 20.

“A reasonable jury could conclude that it was Camillo and Kriskey who were responsible for the publicity surrounding Kordick’s involvement in the signs and any interruption of the Police Dept operations and consumption of resources were in response to their complaints to the GPD, not Kordick’s exercise of his free speech rights…” Krumeich writes on page 21.

Further, he writes, “A reasonable jury could conclude that the Trump/Camillo signs were not ‘deceitful’ or ‘fake,’ but an acceptable politcal parody protected under the First Amendment…”

Krumeich says a jury could decide that Kordick’s involvement in the signs did not result in widespread community outrage as the Town contends, but rather protestations, denouncements and outrage aimed at Kordick were driven by a small group of Republicans active in the Camillo campaign.

He writes that a jury might conclude that Daigle as investigator was not independent or objective for reasons including that he interviewed only interested witnesses and was not privy to material information including Camillo’s intention to fire Kordick after he was eleted, …and “was fed information by interested parties that may be seen to have exaggerated Kordick’s culpability and the seriousness of the situation, and received information concerning unrelated investigations and unfounded partisan conspiracy theories.”

In footnote 26, Krumeich writes that, “On Nov 11, Kriskey forwarded to Captain Berry a video about a liberal organization, ‘Indivisible of Greenwich,’ and posited a conspiracy theory that Kordick was acting in concert with that group to attack Republicans.

In footnote 27, Krumeich writes that after Kordick was suspended, “On Nov 12, before Daigle was retained by GPD to conduct his investigation, Heavey forwarded the video to Daigle and passed along certain rumors related to Kordick and expressed negative sentiments later reflected in Daigle’s report and Heavey’s termination letter.”

Krumeich writes that the ultimate arbiter of credibility is the jury. “There is sufficient evidence that may cause a reasonable jury to believe that the investigations and decisions to suspend and terminate Kordick were tainted by political pressure.”

Tortious Interference

Korick has alleged that Camillo and Kriskey tortiously interfered with his employment contract with the Town during the period between Oct 25 when the signs were discovered and Camillo becoming First Selectman on Dec 1, 2019.

Krumeich writes that a reasonable jury may conclude that Camillo and Kriskey had improper motives and used improper means to interfere with Kordick’s contract with the town.

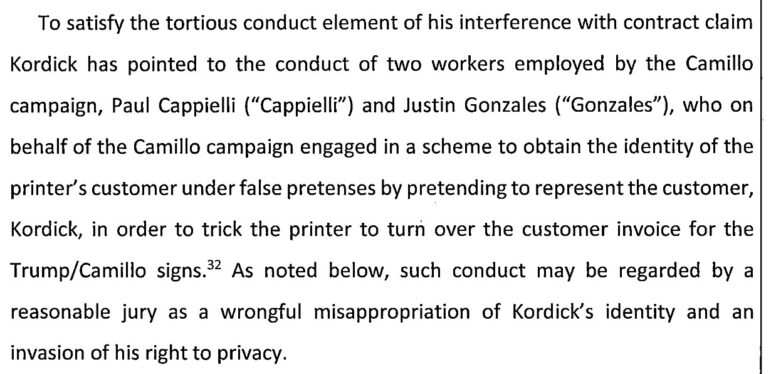

“To satisfy the tortious conduct element of his interference with contract claim, Kordick has pointed to the conduct of two workers employed by the Camillo campaign, Paul Cappielli [sic] and Justin Gonzales, who on behalf of the Camillo campaign engaged in a scheme to obtain the identity of the printer’s customer under false pretenses by pretending to represent the customer, Kordick, in order to trick the printer to turn over the customer invoice for the trump/Camillo signs.”

Krumeich said that conduct may be regarded by a reasonable jury as wrongful misappropriation of Kordick’s identity and an invasion of his right to privacy.

“A reasonable jury could conclude that Camillo and Kriskey, the candidate and his campaign manager, had knowledge of the proposed strategem to learn the identity of the printer’s customer, approved and/or ratified an acted in concert, using as their agents the paid Camillo campaign workers who carried out the wrongful scheme to uncover Kordick’s involvement in the purchase of the Trump/Camillo signs by falsely assuming his identity to deceive the printer into providing the invoice that revealed Kordick’s involvement in posting the signs.”

Krumeich said after receipt of the invoice Camillo and Kriskey could be found by a jury to have acted in concerto to provide a copy to Tesei, the Town attorney and Greenwich Police.

“A reasonable jury could conclude this was done, in part to get Kordick fired.”

Kordick alleges that Camillo and Kriskey knowingly acted in concert to use agents to commit tortious conduct.

“The evidence of misconduct that may be attributed to Camillo and Kriskey by the jury and found to be improper, and may also be found to have caused Kordick the losses for which he seeks recovery and therefore would be sufficient for a reasonable jury to find tortious interference by Camillo and Kriskey with Korick’s employment contract with the Town.”

Invasion of Privacy May Be Accomplished through an Agent

Kordick alleges that Camillo and Kriskey invaded his privacy by conspiring to trick the printer in Texas.

“The allegedly wrongfully obtained invoice was then used by Camillo and Kriskey to out Kordick’s involvement in the Trump/Camillo signs, after the signs had already been removed, which a reasonable jury could find was done to harm Kordick by exposing him to public opprobrium and loss of his job,” Krumeich wrote.

Krumeich said a reasonable jury could conclude that Camillo and Kriskey invaded Kordick’s privacy by disclosing he bought the signs and thereby exposed him to all the negative consequences.

And, he writes in footnote 36 that Connecticut has recognized at common law a tort for invasion of privacy by appropriation of another’s identity.

In footnote 35, the judge writes that Invasion of Privacy may be accomplished through an agent.

Krumeich writes that the jury may find that Camillo and Kriskey obtained a personal and political benefit from their agent’s impersonation of Kordick to the Texas printer.” (page 32).

Lastly, Krumeich writes that a jury could find that the defendants acted maliciously with the goal of getting Kordick fired for his exercise of free speech rights, and that there are genuine issues of material fact concerning Kordick’s claims against Camillo and Kriskey for invasion of privacy that preclude granting their motion for summary judgement in their favor.

Fred Camillo declined to comment for this story citing the pending litigation.

Jack Kriskey replied, “No Comment.”

An email to Paul Cappiali was not returned.

Mark Kordick responded to a request for a comment by saying, “Unlike myself, I am almost certain the defendants will be unwilling to comment on the record for your story, electing instead to hide behind the apron strings of ‘pending litigation.’ It begs the question, ‘What are they hiding?’ If they truly feel they were justified in their words and actions and were comporting themselves in a manner that was above board, they should welcome the chance to explain so on the record. If they are not, which I am certain is likely, that should tell your readers all they need to know.”

See also:

Bogus Camillo/Trump Lawn Signs Whodunnit Rages in Greenwich Oct 25, 2019

Greenwich Police Captain Admits Buying the Trump/Camillo Signs Oct 28, 2022

Trump/Camillo Signgate is Over: Greenwich Police Captain Terminated April 14, 2020