The push for imposing tolls on working people continues this week led by Governor Ned Lamont and state Senator Alex Bergstein, who still supports tolling all cars and trucks, against bipartisan opposition in the General Assembly. Bergstein and Lamont’s case for tolls has always been based on the unproven assumption that there is a major shortage of tax revenue for transportation spending in our state. Five simple facts clearly contradict that premise and the entire case for tolls or other new taxes.

The push for imposing tolls on working people continues this week led by Governor Ned Lamont and state Senator Alex Bergstein, who still supports tolling all cars and trucks, against bipartisan opposition in the General Assembly. Bergstein and Lamont’s case for tolls has always been based on the unproven assumption that there is a major shortage of tax revenue for transportation spending in our state. Five simple facts clearly contradict that premise and the entire case for tolls or other new taxes.

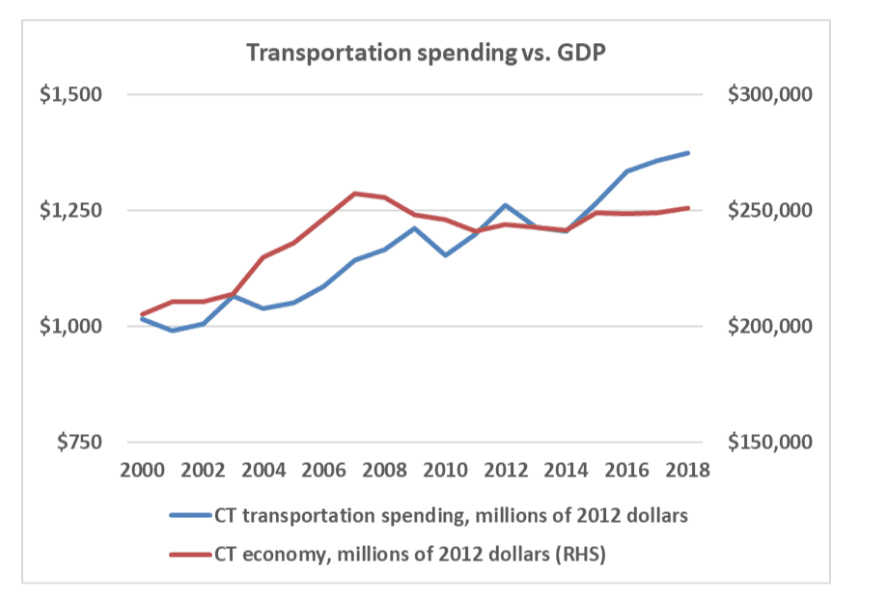

First, transportation funding in Connecticut has increased a lot in recent history—much faster than economic growth and inflation. From 2000 to 2018, Special Transportation Fund spending increased 35 percent compared to 22 percent real economic growth in the state. From 2008, spending increased 18 percent, while the economy shrunk by 2 percent in real terms. Real spending on public transportation more than doubled since 2000, up 106 percent, even as Metro North train times have slowed. Spending has gone up and up, while quality hasn’t, and the state economy has ground to a halt.

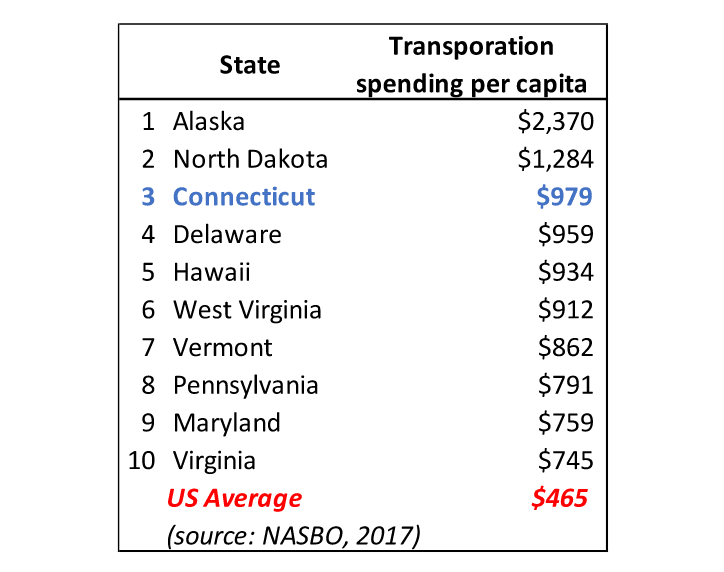

Second, Connecticut already spends a lot more than other states on infrastructure. According to the National Office of State Budget Officers (NASBO), our state government spent the third most of any state per capita on transpiration in 2017 at $979 per person, more than twice the national average of $465. They spend ninth-most relative to state GDP at 1.3%. It’s an understatement to say there is no shortage of funding for transportation in Connecticut.

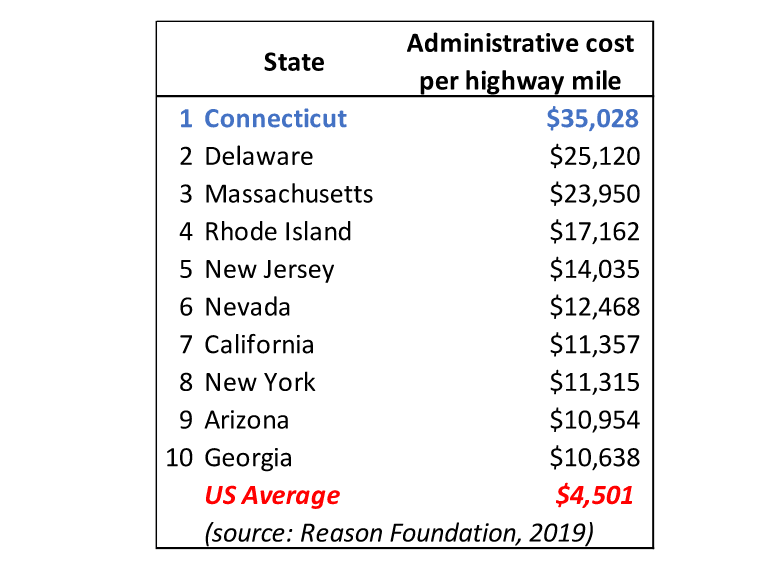

Third, Connecticut gets less bang for its buck than other states on infrastructure. Our state government spends the sixth-most per mile of highway of any state in the country and the most in terms of administrative costs, according to the Reason Foundation. There is some question whether the first statistic fully reflects the inefficiency of the STF, but there is little argument that the latter does not. Not only is Hartford spending too much but its spending it poorly.

Fourth, our state government has spent extravagantly on unnecessary, brand-new transportation projects in the last decade. Just two recently cost taxpayers well over $1 billion. In 2011, the state began spending $567 million to build a duplicative busway over 9.4 miles between New Britain and Hartford (there already existed bus service between the two cities). Today it still spends about $22 million per year subsidizing the busway ($4 million in fares vs. $26 million in operating expenses). Extrapolating November 2019 ridership data, that translates to about a $6.25 subsidy per one-way trip on a $1.75 fare. If you amortize the capital costs over 10 years, it’s a $22.37 subsidy per every single ride. If you subtract the roughly 8,500 average daily weekday riders using the bus before the new busway was constructed, those subsidies rise to $18.14 and $64.90 per new ride acquired, respectively.

The state spent about the same in capital costs beginning in 2010 for the Hartford passenger rail line that shuttles people from New Haven up to Springfield, Massachusetts. In addition to the state’s $564 million of capital costs, the federal government spent $205 million upfront, while the state is now also footing a $37 million annual operating deficit ($7 million in fares vs. $44 million in OpEx)—nearly double what Malloy’s DOT promised. Over 634,000 annual rides, the operating subsidy equates to $57.89 per one-way trip and $146.85 per ride inclusive of the state’s capital costs amortized over a decade.

Bergstein and Lamont’s position implies that Connecticut should double down on all this. But amidst all that heavy spending, Connecticut’s economy was among just a couple in the nation that did not grow at all. There is no evidence that massive infrastructure spending in this state has stimulated the economy. If anything, the evidence suggests higher taxes for wasteful spending has depressed it.

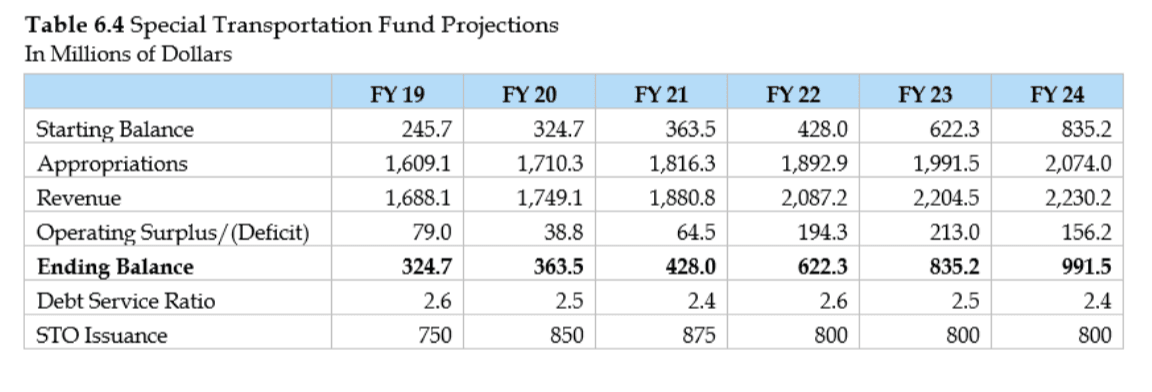

Fifth, toll proponents have failed to justify higher revenue in the future. The state’s budget scorekeeper continues to project the Special Transportation Fund with a positive balance through 2024, when it stops scoring. That means no new revenue is needed, if the state stops diverting transportation revenue to the rest of the budget. Additionally, the Malloy and Lamont administrations have presented constantly changing wish lists of projects from Malloy’s $100 billion, 30-year plan to the Lamont DOT’s $25 billion, 10-year plan, to Lamont’s new $21 billion menu. All of those include inflated cost projections and unnecessary projects—including brand-new train stations on the recently-built Hartford Line.

All these facts indicate that our politicians spend our money recklessly and the bureaucrats manage it fecklessly. It’s about time we stop bailing them out—and reject Lamont and Bergstein’s ideas to take even more from the pockets of working people in our state who are hurting. We can improve our state’s poor infrastructure by reforming how we spend, but not by doing more of the same.

Ryan Fazio is a member of the Greenwich Representative Town Meeting. He tweets about politics and economics @ryanfazio.