This is the second article in the Greenwich Sustainability Committee’s “One Water” weekly series.

Written by Sarah Coccaro, Conservation Resource Manager, Greenwich Conservation Commission, member of the Land and Water sector of the Sustainability Committee

The seasonality of the Northeast is central to the region’s sense of place. Yet, earlier springs and milder winters are changing ecosystems and environments in ways that adversely impact commerce, recreation, tourism, agriculture, industry and livelihoods. Global warming alters nearly every stage of the water cycle; from precipitation, evaporation, surface runoff to stream flow. These changes put pressure on drinking water supplies, food production, property values, and our quality of life. When we talk about climate change, we’re essentially telling a water story.

Connecticut’s climate is changing

The Northeast region is warming the fastest after the North and South Poles. Connecticut’s average temperature has risen 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) since the late 19th century, double the average for the lower 48 states. One way to understand a temperature rise of 3.6 degrees is to think of the Earth as a giant organism that has a regulated temperature, much like the human organism. If the temperature of the Earth rises 3.6 degrees, clearly it has a fever!

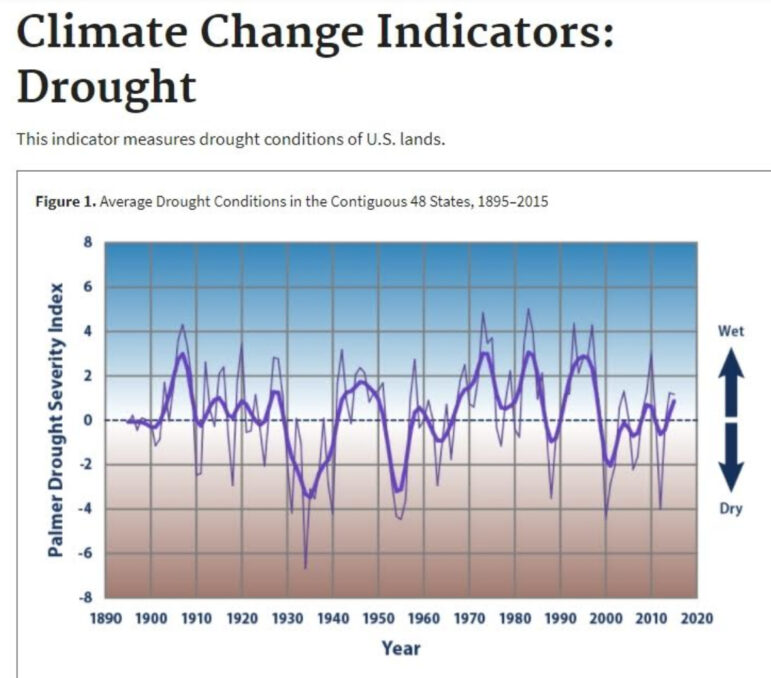

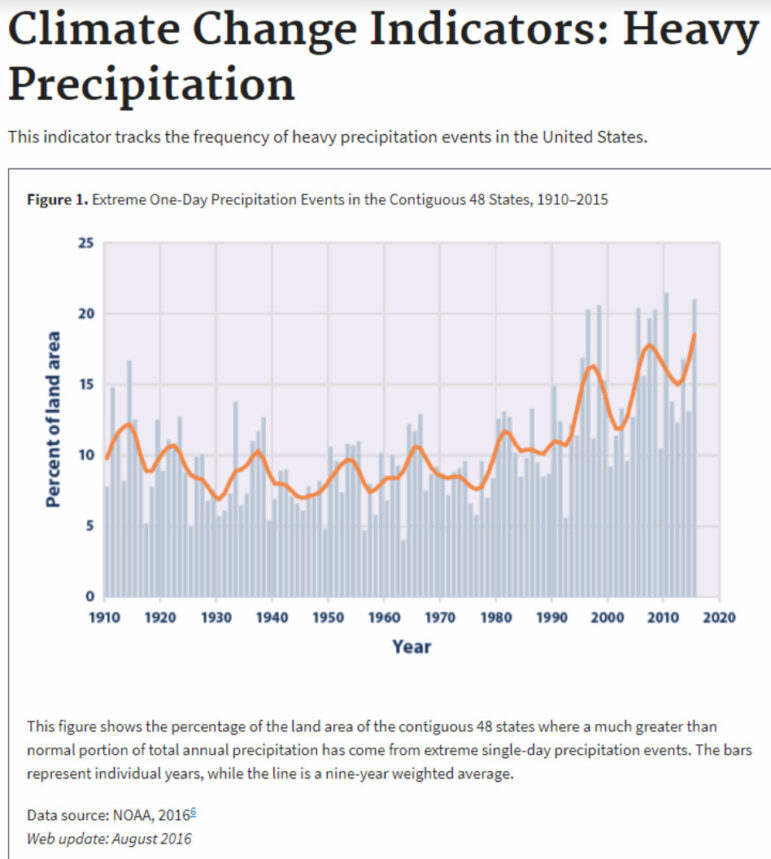

Spring is arriving earlier and bringing more precipitation. Heavy rainstorms are more frequent, and summers are hotter and drier. Droughts and heat waves are more common. Sea levels are rising with severe storms increasingly causing floods that damage property and infrastructure. Water quality and quantity are also being affected. The combination of changes in precipitation and runoff, and the increase in consumption and withdrawal, have reduced surface and groundwater supplies in many areas.

Extreme weather events in Connecticut over the past 10 years have been linked to climate change. The biggest storm to hit Connecticut shores in decades, Hurricane Irene in August 2011, was responsible for over 700,000 power outages, destruction and damage to homes. Not long after, an early snowstorm hit in October 2011, dumping up to 24 inches of snow in parts of the state. Many trees still had their leaves and the weight of the snow felled tens of thousands of trees across the state, downing power lines and blocking roads. Super Storm Sandy touched down a year later, in October 2012, where the storm surge in Greenwich hit over 11 feet. The Town is still closing out the last remaining Hazard Mitigation Grants for homeowners affected by Super Storm Sandy.

Connecticut has recently experienced worrying droughts, including a 46-week statewide drought in 2016-2017, where more than 70% of the state was considered in an extreme or severe drought. Impacts associated with a moderate drought include stressed trees and landscaping, and lake and reservoir levels below normal capacity. Droughts strain drinking water systems by lowering surfacewater reserves and groundwater. The prolonged 2016-2017 drought raised awareness in Connecticut that river basins and tributaries can become depleted, even though water scarcity has not typically been a problem for the state in the past. Many cities and towns declared mandatory water conservation measures, including Greenwich, that are still in place today.

Climate change in Greenwich

Prediction models don’t paint a pretty picture for our climate with many of the same outcomes of heavy rains and longer dry periods. Average precipitation is likely to increase during winter and spring. Winter precipitation may fall more as rain; flooding is likely to be worse this time of year too. Rising temperatures will melt snow earlier in spring and increase evaporation, thereby drying soil during summer and fall. Droughts will be worse during summer and fall with increased frequency, duration, and intensity. Sea level rise may increase by 12 to 23 inches by the end of the century. There will be more coastal flooding caused by extreme storm events. Temperatures may increase by 4 to 7.5 degrees Fahrenheit by the end of the century, or within the lifetimes of our grandchildren. The number of days that will feel hotter than 90 degrees in Fairfield County will increase from 15 days today to 49 days by mid-century and 80 days by the late portion of the century, posing unprecedented health risks and making our dependence on water even more acute.

Scientists have already observed species starting to shift their geographical ranges in response to climate change, and rapid warming in this region could make those shifts happen even faster.

Once the backbone of New England fisheries, cod haven’t made the expected comeback from overfishing due to warming waters and the collapse of the lobster fishing industries are blamed on rising Long Island Sound and Atlantic Ocean temperatures. Aquaculture farms are especially vulnerable to climate change as organisms and operations are exposed to temperature and chemical fluctuations in the water.

Scientists believe there may be greater impacts to shellfish aquaculture, such as clams, oysters and mussels, compared to fin fish production. Shellfish are especially impacted by warming water and nonpoint source pollution resulting in the loss of natural buffers to our shorelines from big storms.

What does all this mean to me?

It means hotter weather, beaches and lakes closed to swimming, downed trees, power outages, long heat waves and dangerous weather conditions. It means stress on our Town’s budget, infrastructure and economy. It means a loss to the overall quality of life. It means our trees and forests will suffer (along with their ability to buffer rising temperatures) and some streams will disappear along with the wildlife that depends on them. Local officials are already planning several initiatives aimed at making the Town more resilient to climate change, including a project directly related to our Town’s shorelines, tidal ponds and infrastructure.

There are things everyone can do to help conserve water, like taking shorter showers, fix leaky plumbing, water and mow lawns less, transition lawn space to drought-tolerant plantings and maintaining chemical-free lawns. More so, reducing food waste, composting food scraps, and even avoiding foods, like beef, that require a lot of water, all help to reduce water consumption. Increasing water storage (rain barrels or rain gardens), making irrigation systems more efficient, and making sure crops are appropriate for the local climate are a few ways municipalities and individuals can help to prevent water stress.

This video is helpful in understanding the importance of the water cycle related to climate change.

Our next article will be “Water in Greenwich: Too Much and Too Little”.

See also:

One Water. Shared: Greenwich Within the Long Island Sound Watershed

March 21, 2021