The fallout continues over a heated exchange during nearly 23 hours of testimony in a public hearing on statewide zoning legislation on Monday.

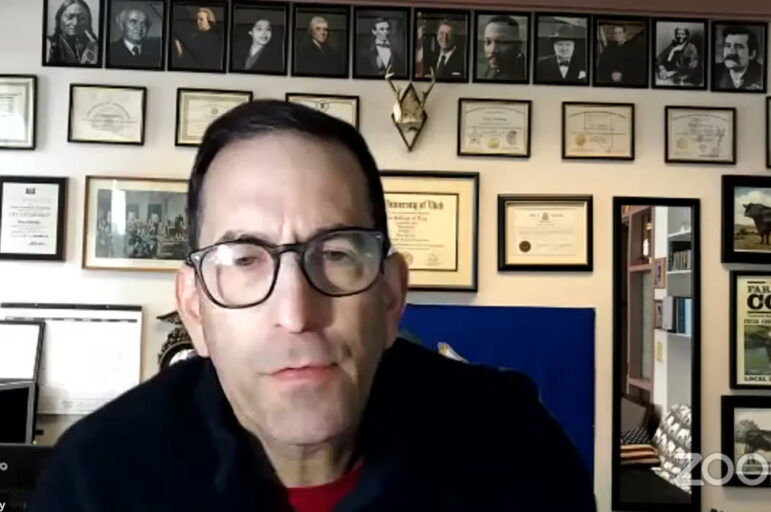

During the CT General Assembly’s Planning & Development committee hearing via Zoom, with over 340 signed up mostly to comment on Senate Bill 1024, the Mayor of New Haven Justin Elicker singled out Greenwich, New Canaan and Woodbridge for criticism.

“Connecticut is one of the most deeply segregated states in the nation, both as a result of history and contemporary policies that exacerbate economic and social equality. The exclusionary zoning codes of so many CT towns are perpetuating this,” Elicker said.

“Using local government to dramatically restrict what housing is available, regardless of the significant demand for it, is having devastating implications,” the mayor continued.

While no one disagreed that towns in Connecticut have a past history of discriminatory zoning, many argued that the proposed legislation would not make Greenwich more affordable, and would result in unintended consequences.

In Greenwich, where a .1 or .2 acre lot located downtown with a “tear down house” fetches well over $1 million, some argued the result of SB 1024 would be a proliferation of expensive condos or rental apartments.

Rather than create affordable units, it would instead erode what remains of downtown’s middle class housing stock.

Mayor Elicker described 1024 as a thoughtful and moderate reform that would “quickly” create more housing in the places that make the most sense – near transit and commercial corridors.

“Black people have been systematically kept out of areas of greater opportunity. In many instances, zoning codes were and are still designed to keep white towns white, and keep poorer residents segregated to dense underfunded areas of the state,” Elicker continued. “Housing is one of the most effective tools to creating economic opportunity and mobility. That is why this tool has unfortunately been used throughout history to stop Black residents from accessing housing.”

SB 1024 was largely crafted by DeSegregate CT. Sara Bronin, its founder, has said her group was an outgrowth of the Black Lives Matter protests against police brutality last summer. She said the legislation would result in overall increased housing supply, which would in turn result in reduced cost of housing, a more diverse housing stock and the preservation of farmland by curbing sprawl.

People opposed to 1024 pointed out it does not mandate Affordable housing, except when a development has at least 10 units. At that point, 10% must be “Affordable” per the state formula.

Instead, the legislation makes multi family housing “as of right” in each town’s 1/4 mile “Main Street” and 1/2 mile radius of each town’s designated “transit district,” which in Greenwich would likely be the main Greenwich train station, based on the assumption that increasing the supply of units would result in lower prices.

Western CT Council of Governments (WESTCOG) director Francis Pickering, whose testimony is available online, questioned the bill’s premise, saying it would be counter productive “to compel municipalities to allow denser housing around transit stations and commercial corridors – places where a car is not necessary and that are ideal for households that struggle with the cost of owning one – by right, at market rate, without any affordability requirements.”

“This would pull the rug out from under the region’s successful inclusionary zoning programs,” Pickering said.

Reaction to Elicker’s comment was swift.

State Rep Doug Dubitsky, a Republican who represents nine small towns in the northeast of Connecticut, said to Mayor Elicker, “You just said zoning regulations are being used by towns to keep people of color out. Name one.”

“There aren’t explicit policies, but it is clear that it is near impossible for certain people to live in certain communities because of the zoning regulations,” Elicker said.

“I can’t live in Greenwich. I can’t afford it,” said Dubitsky. “It’s because of my income. You made a very blatant statement that there are towns and cities in this state currently, as of today, are using zoning to discriminate against people of color and to keep them from moving into their towns. Name them.”

Elicker said, “Income is related to someone’s ability to access housing and to move into places like Greenwich.”

“Of course it is,” Dubitsky said. “I can’t move to Greenwich because I can’t make enough money. It has nothing to do with the color of my skin.”

Elicker dug in. “As a white person that grew up in a privileged background, that had enough funding, a stable house under my head to allow me the ability to get enough revenue to live in stable housing. The history of many, many Black people in the state of CT and around the nation is just the opposite. It’s all of our responsibility to work to undo that.”

“You’re skirting the question,” Dubitsky said. “You made a bold statement that there are towns currently, as of today, discriminating against people based on the color of their skin, by use of zoning regulations. I challenge you. Name those towns.”

“Historically it was done explicitly,” Elicker said. “Today it is done in a more creative way. But it still exists.”

“Where?” Dubitsky pressed.

“In many of the suburban towns in our state,” Elicker replied.

“Which ones?” Dubitsky asked.

“Greenwich, New Canaan – you name it,” Elicker said.

“So Greenwich and New Canaan are now actively discriminating against people of color with their zoning regulations?” Dubitsky asked. “Is that your statement?”

“Correct,” Elicker said. “There are many towns around the state that use zoning to prevent poor people, including, because average median income is low for people of color, from moving into their towns.”

“You’re now mixing poor people and people of color,” Dubitsky said. “Are you saying they’re the same thing?”

“No, I am not, but the median income of Black residents and Hispanic residents in the state is much lower than white residents. The zoning policies are perpetuating segregation.”

Rep Fiorello, who is a member of the Planning & Development committee, asked Mayor Elicker for evidence.

“Are you under the impression that Greenwich is all white?” she asked.

“No, I am not, but it is predominantly white,” Elicker said.

Fiorello said Greenwich’s Hispanic population was close to 30%.

“Are you aware of that?” she asked.

“I’m not aware of the specific statistics around Greenwich,” Elicker said.

“Greenwich is very diverse. It’s 27% non white. Is that not enough?” Fiorello asked. “You made an incredible accusation against my town.”

“Places like Greenwich, Woodbridge and New Canaan are using zoning to keep out communities of color,” Elicker said.

The mention of Woodbridge was significant.

That town is being sued by a group whose leaders include Yale Law School professor Anika Singh Lemar, the wife of Democratic State Rep Lemar (represents New Haven, East Haven), who strongly supports 1024.

According to CT Mirror, Woodbridge has “virtually no affordable housing. Woodbridge continues to prohibit multi-family housing, 1.5 acres is required to build a single family home nearly everywhere in town, and only 35 housing units in town are reserved for low-income residents – nearly all of which are solely for elderly residents. In the last 30 years, just three two-unit homes have received a permit to be built, compared to 281 single-family homes.”

Like Woodbridge, Greenwich does have large lots. There are 2-acre zone and a 4-acre zones in “back country,” but closer to the increasingly desirable “front country” – areas along the Post Rd, I-95, rail line and shoreline – there are zones with small lots and two-family zoning.

Testifying prior to Elicker, Greenwich First Selectman Fred Camillo, formerly a State Rep himself, said the prospective legislation neither addressed social equity, nor promoted affordable housing.

He said Greenwich’s P&Z commission was planning next week to present to the Board of Selectmen a proposal for an affordable housing trust fund based on fees collected from developers, and that in the last five years alone, the town’s housing authority had spent $27 million on affordable housing units.

He described the town’s increasing diversity, both ethnically and socio-economically.

Camillo said the Town of Greenwich had seen an increase in the non-white population of 25% since 2000.

He noted that about 27% of the town’s population of 63,000 fell into the ALICE category, which is short for Asset Limited Income Constrained Employed.

He added that over 38% of the town’s public school population was non-white.

In Greenwich, the percentage of public school students who qualify for free and reduced lunch hovers at around 20%.

The district has four Title I schools.

About 4.5% of students are English language learners.

The responses to Elicker’s comments were swift.

Dan Quigley, the RTC Chair issued a letter referred to the zoning legislation’s intent as being “sinister.”

“The real focus of this legislation is to add an oversupply of housing to Fairfield County communities, thereby driving down home prices, and making housing more ‘affordable.’ It is not an exaggeration to say that this premise is insane.”

Quigley also asked, “Where is Steve Meskers and Alex Kasser? They love to talk about national politics, but both have been silent on this extremely important local issue.”

The DTC chair Joe Angland issued a statement, saying State Rep Meskers and State Senator Alex Kasser had not been silent.

“In public speeches and emails to constituents they have opposed the very proposals that Mr. Quigley attacks in his letter,” Angland wrote, adding, “…rather than simply wailing ‘local zoning is collapsing’ in Chicken Little-like fashion, they have actually been working the problem.”

Steve Meskers wrote on Facebook that although he believed the goals of increasing affordable housing stock were necessary and laudable, they required a local solution, not one imposed from the state.

On Wednesday, Camillo said he had spoken to Mayor Elicker on the phone and looked forward to working with him in the future. However, he described Elicker’s statements on Greenwich’s zoning as “off base, inflammatory and divisive.”

After demands for an apology flourished, Mayor Elicker issued a statement on Thursday.

“I will not apologize,” he said.

“We live in one of the most segregated states in the nation. There is a history of explicit racism in all towns in our state – Greenwich and New Haven included,” the mayor added. “Today structural racism persists throughout our state. The difference is that some communities like ours in New Haven are working to address it, and other communities like Greenwich and many other Connecticut towns are fighting to protect zoning regulations that perpetuate structural racism.”

All the written testimony from Monday’s Planning & Development hearing is available here.

See also:

CT Sweeping Zoning Legislation, SB 1024, Aims to Increase Overall Housing Supply

A Window into the Crafting of DeSegregate CT State Zoning Legislation