This story is based on an interview spring 2022 in Greenwich and a 2000 interview as part of George Chelwick’s life story.

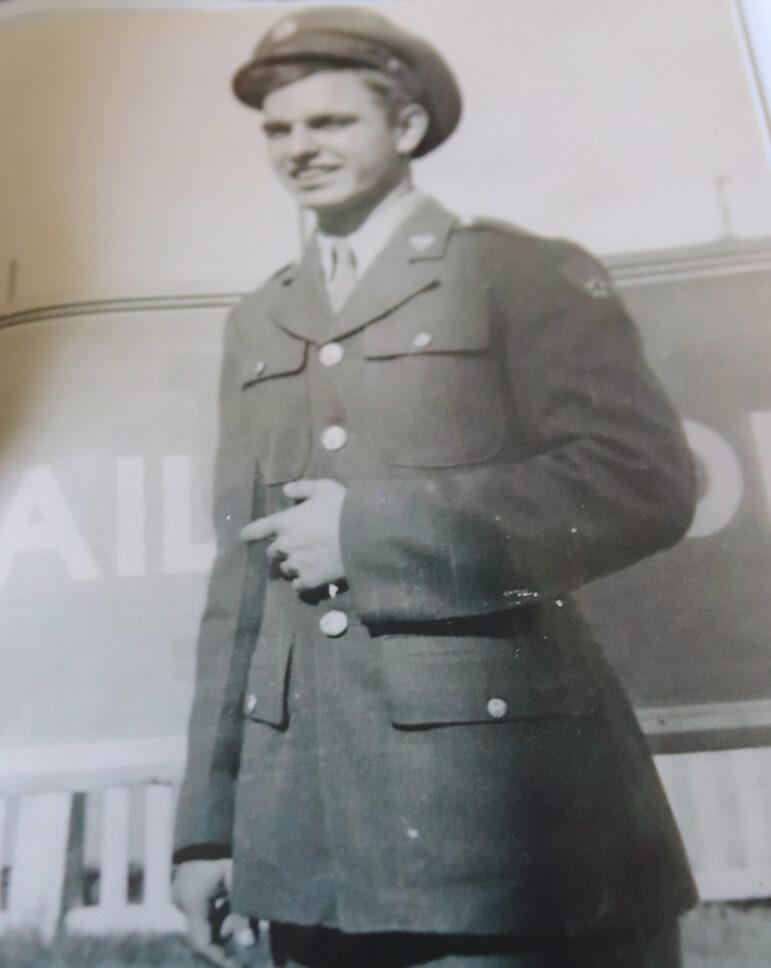

World War II veteran George Chelwick, a Greenwich native turns, 97 this month.

Many who know George recall the many years he volunteered to film Greenwich High School football games.

Not everyone knows he has been married to Nancy for 73 years, had a successful banking career and was inducted into the Army Air Force at the age of 18.

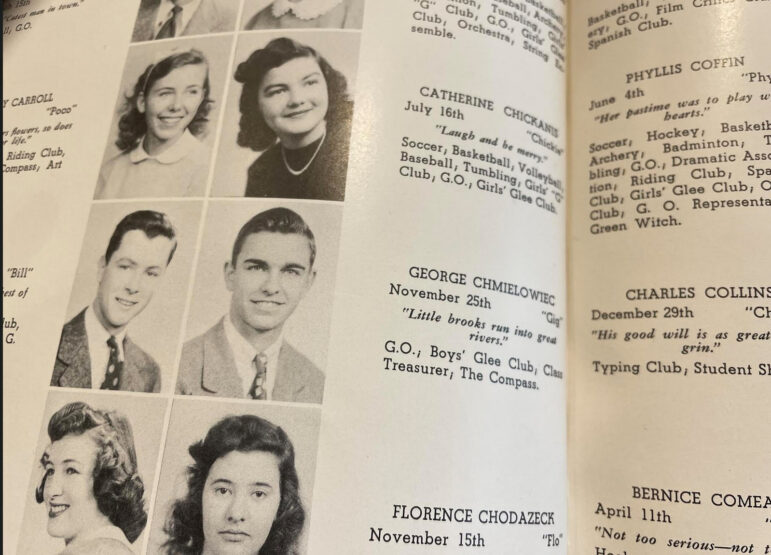

Chelwick graduated GHS in 1943 when the school was located on Field Point Road, the present day location of Town Hall.

He enlisted in March 1944.

D-Day was June 1944.

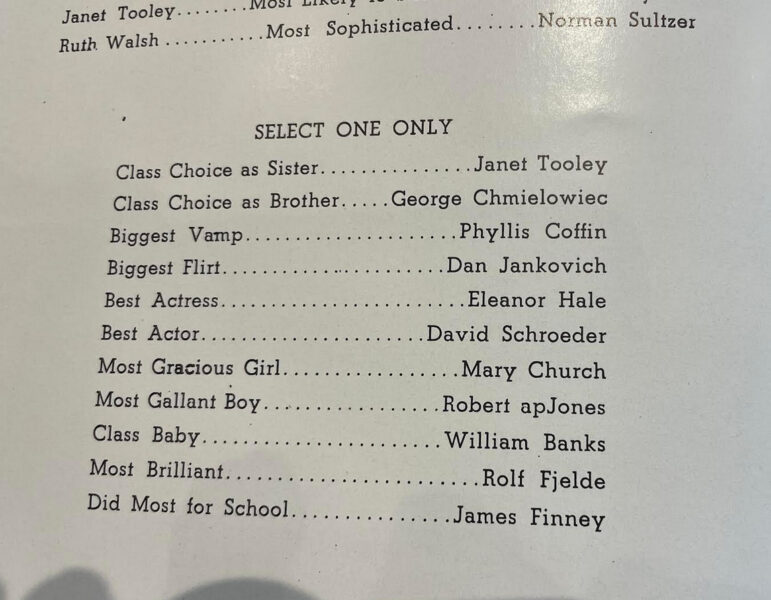

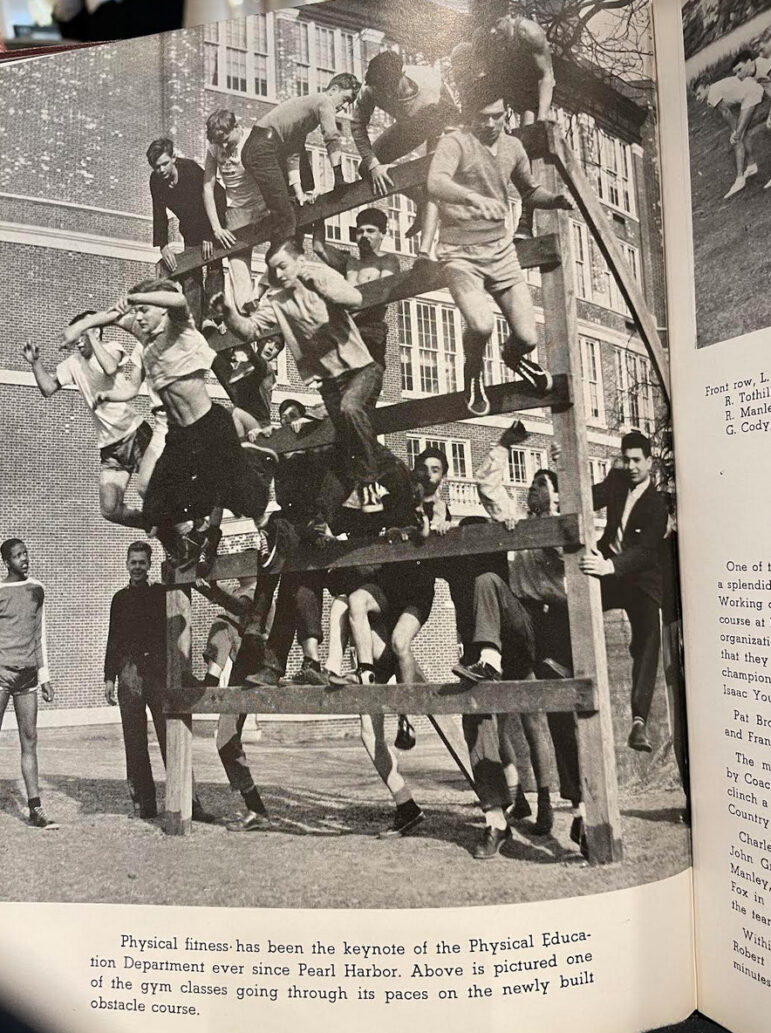

Looking back at the GHS Compass yearbook for 1943, the effort to support the war is impossible to miss, and many pages are dedicated to the Victory Corps.

The Victory Corps was started December 7, 1942, on the first anniversary of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Its primary purposes were to give all possible student aid to the war effort, and to train its members to take their places in war industries or the armed forces after graduation.

Although the Victory Corps movement was government sponsored and nation-wide, GHS used its discretion and initiated its own activities.

VC activities included jobs vital to the war effort. Students participated in civilian defense activities including “Air Spotters.”

War courses prepared students for future induction or war work including everything from pre-flight to cooking, including such “valuable possibilities as boxing, chemical warfare and marksmanship.”

The Surgical Dressings group made thousands of bandages, and the yearbook notes the time they made 400 dressings in one day.

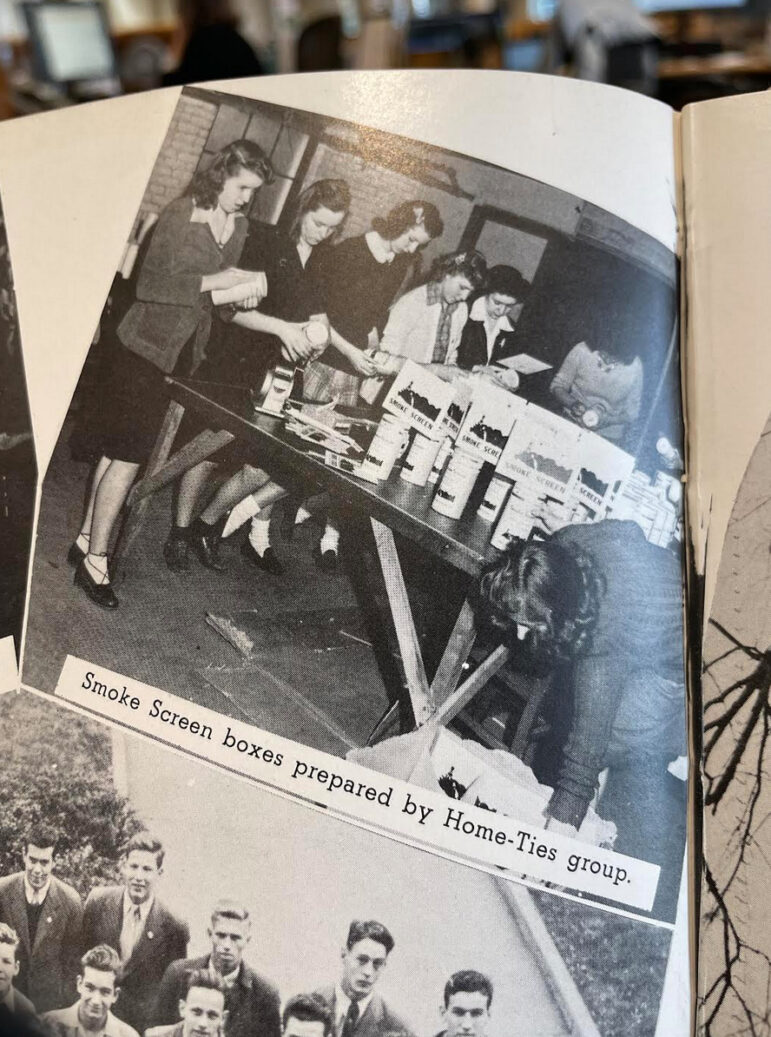

The “Home Ties” group kept in touch with 350 GHS men in the service. George recalls receiving their Smoke Screen “care packages” containing cigarettes and pipe tobacco.

As for George, he set off with the intention of becoming a fighter pilot, having learned about Aviation at GHS.

He recalled his instructor was Zigg Zaranski and that there were eight students in the class.

“At Havemeyer Field at one time there was a small aircraft and we had a class in piloting and plotting a course,” he said. “You had to be concerned with speed and direction of the wind.”

He also remembered the sendoff he received in Greenwich, back when “support our troops” were on everyone’s lips.

George was friends with Lou and Augie Caravella. He remembered how their mother treated every young man who was entering the service to a full Italian dinner of at least five courses: salad, soup, chicken, sausage, meatballs, and pasta.

George enlisted in the Army Air Force and was sent to Fort Devens in Massachusetts in March 1944. Barely passing the height and weight requirements of 5’4″ and 105 lbs, he recalled the overcoat he was provided came down to his ankles.

At Fort Devens, George’s anecdotes range from cringe worthy to hilarious.

He described the experience as something of a cross between camping and college. There was a great deal of testing and training, but there was also rough, crowded accommodations and, he said, if you volunteered for a task you might regret it, but if you didn’t, the consequences might be worse.

Just two days in, George recalled lining up with other recruits when the sergeant in charge asked, and then pleaded, for a volunteer typist.

George, having barely passed typing at Greenwich High School, confessed he had been advised to position himself about two-thirds to three-quarters of the way back in line, since volunteers were typically pulled from the front or the back of the line. He kept his typing skills silent.

Finally, when the sergeant said the situation was an emergency and the volunteer would get a full day off as a reward, George raised his hand. He typed up an inventory of shipping data for 18 hours, finishing in the middle of the night, and only having had a break to use the bathroom.

Much later, George said he realized, based on the date of the assignment, he had typed a list of munitions for D-Day in France in June 1944.

“I guess it is okay to volunteer sometimes,” George said.

At basic training in Greensboro, North Carolina, George described 17-mile hikes and camping with a night’s sleep of just three-hours.

“I carried the same load as the big guys, which was a rifle, bayonet, helmet, full canteen and half pup-tent with stakes,” he recalled. “Actually I remember it was no great difficulty, but it was strictly GI to bitch and moan anyway.”

“Yet, one guy who was twice my weight and well over six feet was practically blubbering. I really wanted to smack him with my rifle.”

After basic training George was assigned a job at the camp stockade where GI’s who had committed various crimes were sent.

“The stockade had towers at each corner, with lots of barbed wire,” he recalled.

George was provided a club an a whistle, stationed inside with the prisoners, and told to blow the whistle to alert the guards if there was trouble.

One night, positioned at the entrance to the mess hall, he encountered a towering man who had allegedly assaulted someone who had later died of his injuries.

“He looked down at me and asked in a loud booming voice, ‘What you going to do with that whistle, boy?'” George recalled. “My immediate response was, ‘I think I’ll swallow it.'”

“With that he laughed out loud and boomed out, ‘This boy’s okay, we’re not going to have any trouble.'”

At Fort Devens, George recalled being crushed to see about 40 names, including his, posted on a board of those rejected for pilot school. “They said, ‘There are alternatives for you.’ I said, “No, not for me. I signed up to be a fighter pilot.’ That was my wish.”

George said he was offered opportunities to be a gunner or a bomber, but insisted he wanted to be a fighter pilot.

“So they tested my aptitude and they said, ‘Oh boy you have mechanical aptitude,'” he recalled.

And, he learned if he kept his marks to the top 25% he could go to electronics school and then on to radar school, “the elite.”

“Radar was a big deal then and TV was a government working project,” he recalled, adding that he learned to make a transmitter/receiver for Morse Code.

Some of the best details of George’s years in the service were of his days off.

One weekend, he and a friend hitchhiked to Milwaukee with just 60¢. He described the generosity of strangers who treated them to meals, drinks, taxi rides and nights out dancing.

“When I got back I still had 50¢ left,” he recalled. “And, boy did I have a great time.”

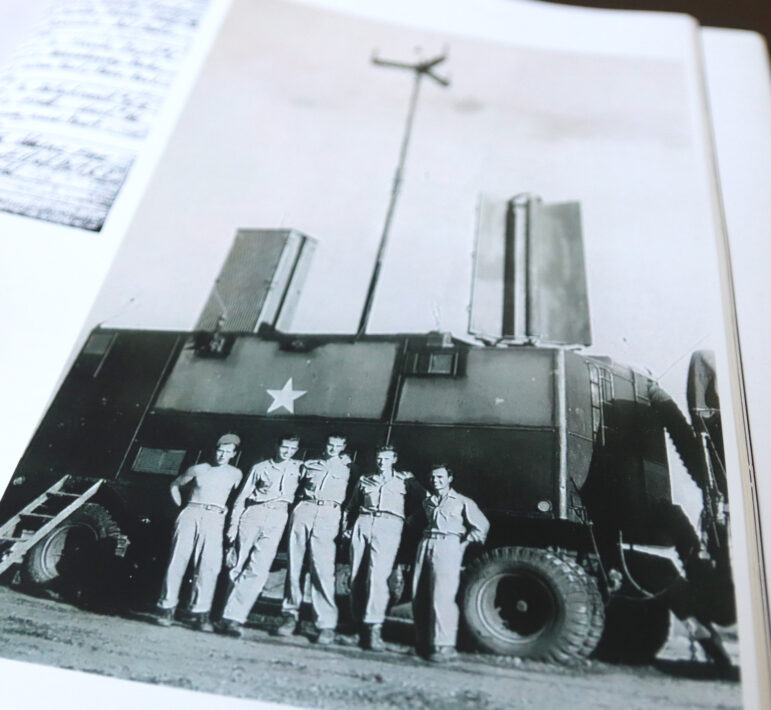

At radar school, George wanted to become part of what was the highly secretive and elite GCA, short for Ground Control Approach. GCA was a radar system for guiding aircraft in for blind landings. For George this meant staying on the ground and instructing pilots through blind landings. He learned he needed to score in the top 10% of his class, which he did.

He was sent by train to Boca Raton, Florida for GCA training involving simulations of plane landings. He said he vividly remembered seeing palm trees for the first time, and receiving those “Smoke Screen” care packages the Town of Greenwich sent.

In 1944 radar was still very secretive and classes were held in a compound with barbed wire similar to the where George was stationed with a club and a whistle.

The trailers were air conditioned, which was a plus, but it wasn’t for the trainees’ comfort. The vacuum tubes and equipment would otherwise get dangerously hot.

George was then sent to Fort Dix, NJ, for live training – no more simulations – and also spent two weeks at Mitchel Field in Hempstead Plains on Long Island. During those two weeks each radar trainee was given a turn going up with a pilot in a two-engine bomber training plane.

George said that particular pilot was about to be sent overseas and took some liberties.

“That pilot was out for a joyride,” George recalled, adding that they flew across Long Island Sound toward Connecticut.

“What were they going to do, court–martial him? George asked. “He said, ‘I’m going to fly around a bit.’ I pointed out Tod’s Point and said, ‘That’s my town!'”

The pilot flew George over his beloved Greenwich, including Island Beach, Indian Harbor, Greenwich Avenue and Greenwich High School, before flying over Manhattan and past the Empire State Building.

During this time on Long Island, George was able to spend a few weekends with Nancy, 16 at the time. He still recalls their painful farewell in Penn Station.

En route to the Philippines by way of California and then Hawaii, George said he was flown in what felt like first class.

His overseas team #28 and comprised of 16 men plus one officer. George, now a “vertical operator” trained in both radio and radar, recalled an Army bus trip on Saipan Island in the Philippines, which had recently been recaptured from the Japanese. He described a mountainous area with cliffs where many Japanese jumped to their deaths rather than surrender.

On the way back to the base he saw a beach that appeared “shiny and bright.” Later, walking on the beach he said it was covered in brass shells, an “indication of the battle and action to take the island.”

Arriving at Nichols Field in Luzon, near Manila, George’s team was told they were the first unarmed passenger transport to arrive. He described smoldering fires and plenty of shell holes and debris.

“The Army was still after pockets of Japanese units and hidden hold-outs that buried themselves wherever,” George said. “At night they would pop up and shoot any of our troops they could find.”

“It was 1945,” George recalled. “Germany was winding down, but the Philippines campaign was still going strong.”

George’s unit was trucked to a camp on the outskirts of Manila to wait for their equipment to arrive.

At night they slept in tents while Filipino guerillas guarded the camp.

“Japanese were still on the ground and coming out at night and taking pop shots,” George said, adding that they were warned that if they heard gunshots to stay silent and roll off their cots and into the drainage ditch.

All of this was difficult to reconcile with the newspaper accounts in San Francisco saying that “all was secured near and around Manila.”

At one point, George’s unit was trucked to a warehouse in the center of Manila where George volunteered in the motor pool doing maintenance in “the grease pit.”

The warehouse was next to an abandoned residential property that was walled in and featured a swimming pool. After work each day, George recalled that a swim was in order.

After a particularly rowdy splashing contest among mechanics, George noticed his pinky toe was at a 90° angle. Off to the G.I. hospital he was sent for what wound up being a memorable stay in an open ward of 50 beds.

During those nine cushy days, likely the result of an error, George said one particular experience convinced him of the value of the USO male entertainers.

A soldier in grave condition who had been shot three times while patrolling during a cleaning out of surviving Japanese on Corregidor Island. After having undergone multiple surgeries, the soldier was assigned the cot directly across from George.

George said the man had been staring blankly into the middle distance, but returned to life after a USO entertainer strummed his guitar and sang, “This Land is Your Land” over and over.

A few days later, with his arm in a sling and bandages around his chest, George said the soldier slipped out of bed to a courtyard where a basketball hoop was set up. He was caught by the nurses shooting baskets with one arm.

George said, “The nurses had a fit, but were well pleased with his stamina and recovery.”

The turning point also marked the end of George’s “fabulous” nine days. He was returned and assigned a new duty to help with the unloading of shipments of supplies onto trucks in the Port of Manila.

He opted for the night shifts which were cooler, though that was when the risk of snipers was higher. George said he would accompany trucks back to the warehouse along with an armed guard.

Eventually George’s unit’s equipment arrived.

In the Philippines there were a few times George crossed paths with other boys from Greenwich. There was a night of drinking with Henry “Hank” Sabetti, a big guy at 200 lbs who had been a star guard for Greenwich High School football team in the late 1930s/early 1940s. George said Hank’s engineering unit was stationed north of the bay in Manila.

“After uncounted drinks I experienced my first awareness of Malaria,” George recalled.

Some people who have malaria experience cycles of malaria “attacks.” An attack usually starts with shivering and chills, followed by a high fever, followed by sweating and a return to normal temperature.

“This illness had evidently a firm grip upon Hank,” George said. “I was told that whenever he drank, he would sooner or later get the ‘shivers and shakes,’ whereupon Hank started in with such violent ‘s and s’ that his cot did a dance, even with his substantial weight.”

“As Hank did not back down on the field of play, he did not back down in service to his/our country,” George said. “It was evident that a quick ticket Stateside because of his illness was within his grasp.”

George recalled that a short time after their night of drinking, Hank’s unit was shipped out to Okinawa where there were horrendous Kamikaze air attacks.

“Hank survived,” George said.

Sabetti lived until 2012, and died at the age of 88.

George recalled encountering a “Pemberwick” fellow, Dominick Fado, in mess hall line one day.

“We were both sporting mustaches, so it took a couple of double takes before full recognition set in,” he said.

And there was the time George volunteered to pick up mail at the base post office and spotted the corner of a Greenwich Time newspaper poking out from a stack of mail.

When he asked who the newspaper was for, he was told it was for Herb Knox of Old Greenwich, a LORAN (short for abbreviation of long-range navigation, land-based system of radio navigation) radio beam operator/mechanic, who turned out to be about 100 yards from George’s tent.

“Herb and I got acquainted, but not for long. He was shipped out to another location very soon.”

George said he didn’t see Herb again until Stateside when Herb invited George to dinner with his family in Old Greenwich.

George’s GCA unit saved dozens of lives. Multiple planes were spared as well.

By January 1, 1946 his unit had saved 78 lives, which George knew because he’d written about it to his sister, who had saved all his letters. The final count of saves, however, was not officially recorded.

While George recalled some crashes and deathly explosions, he said there remained much free time to pass with chess games, card games and movie nights. There was time for letter writing and reading books, including PG Wodehouse and historical novels.

While George’s unit was mercifully air conditioned, and they could always keep their beers cold, it was quite hot in the Philippines. He recalled someone in his unit sunning himself on a cot one day and the thermometer reading 143°, and another time George climbed a fight of stairs and blacked out from the heat and fell backward onto the sidewalk.

“This knocked the wind out of me, plus!” he recalled.

George noted that everything in the service was done “by the numbers,” including calculation of whose turn it was to go home. When he finally saw his name posted on that enviable list, he was trucked to the dock where an ocean-going ship, the General Star, awaited.

He said unlike his plane rides to California and on to Hawaii and then to the Philippines, which “felt like first class,” the return trip was another story.

“Into the ship’s hold, well below deck, no luxury here, no view, four metal pipe-stacked canvas cots filled the hold. There was no good ventilation, only the circulating of various unpleasant odors,” he recalled. “Most of us had the super blitz, ‘two-way G.I’s’ from some lousy chicken.”

It took 17-1/2 days from Manila to Oakland, California, and orders were to go to Fort Dix in New Jersey for discharge.

“As I was the first one on the list and a Sergeant, I was given the box with each man’s record/file. My responsibility was to deliver them at Fort Dix, which I did without loss. Yet, we did almost lose a few men who jumped the train at Reno – I guess they were gamblers. Most of them caught up with us at Salt Lake City and the last at Kansas City, MO. Our train didn’t have priority, as we sat side tracked quite often, this helped the delinquents.”

“At Fort Dix we went through the well-known private interview to get us to re-enlist,” George recalled. “Those of us waiting enjoyed the laughter when the ‘Golden Eagle’ question was asked. A gold eagle cloth badge was given as recognition of discharge from the service. This badge was sewn on your shirt and jacket sleeve. Also, we got our certificates, letters and other information about veteran benefits. And, finally, our pay.”

George said when he was home again, finally, his mustache came off quickly, but not until everyone had a good look.

“Ah, youth,” he sighed. “I was but 20 years, plus five months, and still in one piece and, peace to all.”

George’s service was from March 16, 1944 to May 14, 1946. Hh was discharged as Sergeant, Radar Mechanic specialty No. 863.

As a footnote to his 2000 interview, George said there had been many things he had observed that he would not want on the record.

“Some things will remain indelible in my mind. Fortunately, I had only a light touch of anything like the movie ‘Saving private Ryan.'” Also, I wasn’t destined to be a fighter pilot, but ended up saving lives instead, and knowing a little of my own psyche, for this I thank God in all his wisdom.”

See also:

George and Nancy Chelwick Celebrate 70 Years of Marriage June 27, 2019