This is the fourth article in the Greenwich Sustainability Committee’s “One Water” weekly series.

It may feel counterintuitive to think of soil to improve our water supply, but soil plays a critical role in our watershed. Because the soil is largely invisible we tend to think of it as simply the place where plants grow. In fact, soil is a living matrix that absorbs, filters and stores our water. Soil holds the landscape together in the presence of water.

Our water is absorbed through the soil where it is filtered to create clean streams, rivers, lakes, aquifers, wells, and in our case, Long Island Sound. Water filters through the land in a process called soil infiltration. Healthy soil is essentially made by living organisms into a sponge that absorbs water and stores it as a reservoir for plant life to draw on, and to make nutrients available to the plants. Within this soil sponge plants grow stronger, stay green longer, cool and protect the land from erosion.

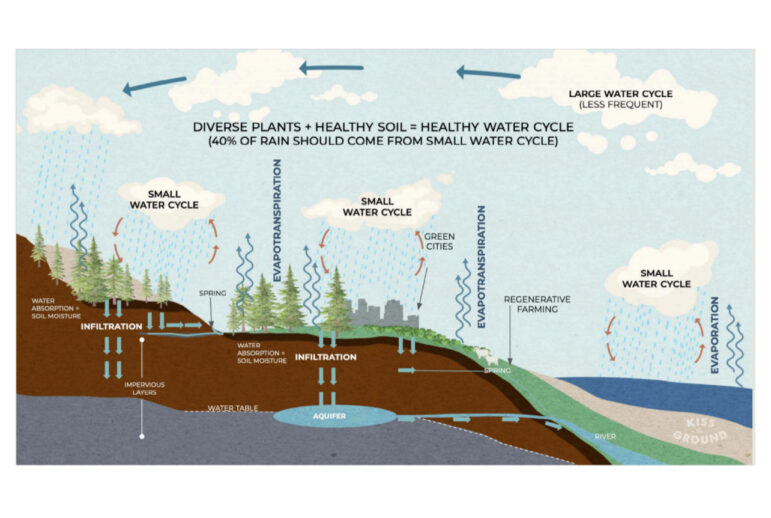

In school we all learned about the water cycle, the dominant paradigm for understanding how water regenerates the Earth’s water system. After all, we only have the water that is here on Earth – there is none falling from space to replenish what is used. We depend on the water cycle to circulate our supply, cleaning it in the process. It is a closed system.

This large water cycle paradigm views evaporation as a loss to the system. However, a new paradigm, where evaporation is understood as the source of all precipitation is called the small water cycle. Although it is called the small water cycle, it is actually more important to local precipitation patterns than the large water cycle. Up to two thirds of precipitation on land actually comes from the small water cycle. It is the small water cycle that is interrupted by human activity, and it is therefore the small water cycle that can be influenced by how we use the land.

When we understand how the small water cycle affects regional weather patterns we can better understand the importance of holding water on the land. When soil holds water deeply, the water is filtered and cleaned. It can then be preserved in our groundwater supply and collect in underground reservoirs called aquifers. When water can’t fully penetrate the soil, excess water runs across the surface of the landscape taking contaminants and sediment with it and often causing floods. And, of course, when water isn’t held by the soil, droughts become more frequent. According to the National Climate Assessment, Connecticut has had a 71 percent increase of rain in the heaviest weather events, the highest in the country along with the rest of the Northeast. This cycle of heavy rain followed by drought is directly related to our soil’s inability to absorb and hold water, carrying enormous costs for homeowners and municipalities alike.

As we outlined in our previous article, runoff has negative consequences for the quality of our water supply. Healthy soil can go a long way to absorbing and holding rain, mitigating runoff and neutralizing the contaminants it carries.

Soil infiltration has consequences for human health because when plants and trees have a stable water supply they grow stronger and are able to release more oxygen, cool the air and absorb carbon dioxide and other pollutants, making the air safe to breathe.

To increase the water-bearing capacity of soil on your property, follow these principles:

- Do not allow the earth to be bare. Keep it planted with native ground covers like wild strawberry, violets, clover and stonecrop.

- Work the soil as little as possible. Lift the soil with a garden fork or make dedicated holes for seeds and plants rather than tilling a large area. Tilling the soil disturbs its structure and damages the underground network of microorganisms that hold the soil together and that allows it to absorb and hold water. Add compost as a dressing and leaves as a mulch and let them work their magic to improve your soil.

- Explore a diversity of native plant species to work the land for you by encouraging beneficial insects that have evolved to resist disease and deter pests.

- Minimize and work to eliminate the use of synthetic landscape chemicals. Pesticides and herbicides damage the soil by killing off microorganisms that feed plants the minerals they need to grow strong and healthy, and can end up in our water supply with real risk to human health.

- Because lawns that are kept cut short have shallow root systems that do little to improve soils, water generally doesn’t penetrate into the ground, but instead evaporates off. Allow lawn grass to grow to 3-4 inches. Taller grass grows deeper roots helping the soil hold more water. Leave grass clippings on the lawn to hold moisture and deliver nutrients to the soil.

- Consider turning a portion of lawn to a more diverse habitat that could include fruit bearing shrubs, native grasses and native flowering plants.

Next in Our Series: “Capturing Run-Away Water”

See also:

The Lowdown on Runoff: Keep Water Clean

April 13, 2021

Water in Greenwich – Too Much? Too Little?

April 5, 2021

Our Changing Connecticut Climate: A Water Story

March 29, 2021

One Water. Shared: Greenwich Within the Long Island Sound Watershed

March 21, 2021