A series on Ecological Landscaping at Audubon Greenwich that was started before the pandemic resumed in person on Sunday, thanks to the initiative of Kim Gregory.

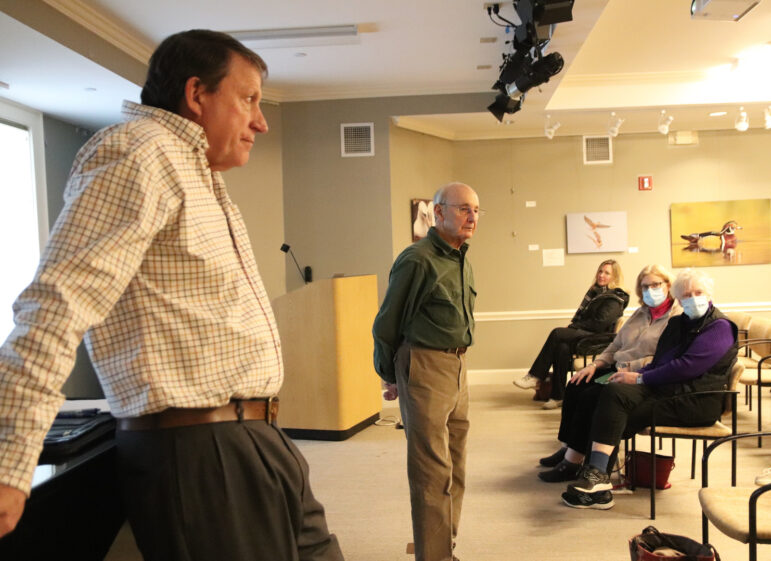

On Sunday, Biologist Jim Carr and Master Gardener Andy Chapin contrasted industrial lawn care with ecological lawn and garden care.

Industrial lawn care typically relies on hired crews, chemicals and loud machinery. With ecological lawn and garden care, nature does much of the work.

“What business does Audubon Center have in garden education when their focus is birds?” Mr. Carr asked. “There has been an alarming decline in the bird population, and one of the main reasons is the way properties are being managed.”

While most people view the perfect lawn as entirely green without a single weed, Mr. Carr said, “There is a high cost in time and money, but the biggest cost is ecological.”

When leaves are ground up by a mower and left on a lawn, along with grass clippings, that provides nutrients to the grass and acts like mulch to suppress weed growth. It also insulate the soil and roots during the winter.

Ground up leaves decompose and add nutrients back to the soil. Then, in the spring there is no need to treat the soil with chemicals.

Industrial lawn care performed by gasoline fueled machinery includes lawnmowers, leaf blowers, de-thatchers, aerators, spraying equipment. The practice also relies on fertilizers and pesticides manufactured on an industrial scale in chemical plants.

An alternative to a green, weed-free and leaf-free lawn is to allow the natural ecology to exist.

The 280 acre Audubon Greenwich nature preserve is an example of ecological management, with its thriving forests, meadows and wetlands.

“I can assure you that no one is out there applying fertilizer to this area,” Mr. Carr said. “Nor is anyone spraying for pests. Yet nature is managing this landscape magnificently, as she does all of her landscapes.”

Mother Nature Recycles Nutrients to Create Humus

In fall dead plant material becomes food for soil organisms. “They ingest it. They excrete it out, and it’s a food chain. Their excretions are a food source for other soil organisms,” Carr explained. “It sounds disgusting, but that’s how nature works. The nutrients move down the food chain and the final use of excretions is humus.”

Carr described humus as nature-made compost.

The production of humus takes place over the winter. In spring it is available to support lush plant growth.

Mr. Carr talked about the importance of biodiversity. The more species there present, the more chance to attract ‘beneficial predators’ who prey on and kill the pests.

Beneficial predators are mainly birds, but also insects.

“In a stable environment where humans don’t interfere, every pest has at least one enemy that wants to make a meal of it,” he said. “They’re not going to eliminate them, but they’ll keep them down so they don’t cause considerable damage.”

Mr. Chapin said native trees add value, and that the primary reason birds show up at Audubon every spring is for the “caterpillar explosion” from native trees. The caterpillars are “protein packs” that give the birds energy.

Industrial Lawn Care: Chemical Fertilizers, Insecticides, Herbicides, Irrigation, Fungicides

Mr. Carr said with commercial lawn care services that practice industrial lawn care, when the lawn is mowed, and grass clippings are bagged and disposed of, nutrients for the soil and trees are removed.

Carr likened healthy soil to a fat, nutrient-rich bank account.

“There are only so many nutrients there. If they keep being removed, it’ll go bankrupt. Those nutrients need to be replaced.”

Industrial lawn care features chemical fertilizers high in nitrogen, potassium and calcium. By law they have to be water soluble, which means they have to be immediately available to the plants.

When there is no humus in the soil, and nutrition comes from fertilizer, plants take up nitrogen faster than it can be incorporated into the tissues of the plant. The nitrogen backs up in the metabolic chain in the plant.

And, since insects need nitrogen for growth and reproduction in the spring, they will go after the free nitrogen in the grass.

“How do we solve that problem? Insecticides,” he said.

Since most people consider a “weed” anything that is not turf grass, they’ll use herbicide.

Then, in summer when lawns begin to dry out and develop a problem with soil acidity, people apply Lyme, when humus would otherwise buffer the acidity.

Humus absorbs water like a sponge and stores it. As the soil starts to dry out in summer, the humus will release the water gradually to the plants, to try to keep an even moisture in the soil.

“Nature really has her act together,” Carr said.

“But if the lawn has been deprived of soil and is missing humus, how is that solved?” Carr asked. “Irrigation.”

Then, when grass dies it creates thatch.

Leaves, stems and roots accumulate when they die and start to clog the lawn.

Enter the industrial lawn care’s de-thatcher, a gasoline powered machine.

“All this organic material that would make nice humus is just taken away,” he said.

Healthy soil is like a sponge with pores. Air circulates, bringing oxygen to the roots and taking carbon dioxide away.

Since there’s no humus in a chemical lawn, there’s no porosity.

If the soil compacts and roots don’t get oxygen, they shorten and ultimately die.

“How’s that corrected?” Carr asked. “Aeration.”

Mr. Carr described aeration as a total waste of time and money.

“If you watch these machines operate, they’re poking holes. Those few holes do nothing, and when it starts to rain, those holes fill up.”

Carr and Chapin’s advice? Allow nature to create humus: Leave grass clippings in place. In fall, don’t blow the leaves; mow them with an ordinary walk-behind mower to grind them up and leave them in place.

When the leaves are ground into small pieces, they break down quickly and will have vanished by spring.

“There will be a little brown in the lawn and some people may object to that,” Mr. Carr said. “But if you can put up with that, there’s absolutely no reason to blow away the leaves.”

Besides, Carr said there has been “mission creep” in the use of leaf blowers, with crews blowing lawns all summer long.

His suggestion was to ask the lawn crews to mow and not blow.

Further, he said many property owners have more lawn than they need for children and dogs, and some lawn can be replaced with ground cover, ecologically managed flower beds and pathways.

Beneficial Predators and Native Plants

A hospitable environment with native plants attracts beneficial predators like Ladybugs and birds, who get energy from the plant nectar, in turn, help control pests.

Also, the insects provide the plant a service by spreading pollen to help the plant reproduce.

“If you use insecticides and kill all the insects, the ones you don’t want will come back faster,” Chapin said. “Within 10 days you have a new cycle of mosquitos with no competition. Meanwhile the average dragonfly life cycle is two to three years.”

Some beneficial predators will overwinter inside dead flower stems. Some will lay eggs in leaf litter.

So Mr. Carr recommends not cutting down dead flower stalks because they provide shelter for beneficial insects over the winter.

Interested in pursuing ecological landscaping? On Dec 11 from 1:00-3:00pm, Carr and Chapin will lead a session at Audubon on how create your own ecological garden.

The event is free but registration is required. Register by emailing [email protected]