By Andrew Melillo

In the historical editorial dated November 12, 2020 titled, Steep Hollow

– What’s in a Name: The Old Bridge is Gone – the author asked the question: What’s in a name? The answer was quite a lot. Quite a lot of history and energy lies behind a simple name. But what else is in a name? A little bit of folklore. For 113 years – Steep Hollow, or North Mianus, or Cos Cob, and the Old Bridge did not have its complete history being told.

These forgotten names and events were brought to light once more after Missy Wolfe did her own research. It was through that effort that the old works of Daniel Merritt Mead, Spencer Percival Mead, and even the works of Lydia Holland and Margaret Leaf were further built upon, and in some places, amended – so to establish a much more accurate history of the Town and the Founders of the First Society (Old Greenwich). What is in a name? A bit of folklore, a lot of history, but also a lot of forgotten or hidden history…and that is exactly what Missy titled her book, Hidden History of Colonial Greenwich.

Remembering the account of John Mead and the old Quaker (who professed to read men’s thoughts – not a quality of which Puritans approved) on his way to the grist mill, Spencer Percival Mead (of which he is the only known source for this anecdote), wrote:

At last they came to the brink of the Mianus River. Here the Quaker was really in trouble. How to cross a river, two or three feet deep….

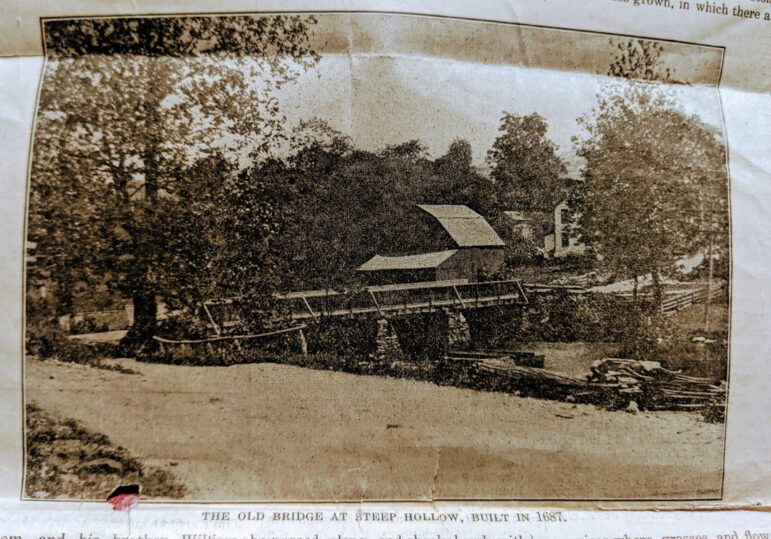

It was at this spot that the Townsmen recommended the need to construct a bridge, and it was subsequently voted on and approved. As Spencer Percival Mead writes in his book, and as the 1907 article from the Greenwich Graphic echoes (even the history boards installed on the corner of Palmer Hill Road and Valley Road repeat the same story) – that the bridge was constructed by brothers Gershom and William Lockwood. It was this bridge that was the same bridge used to construct the foundations of the present new one. A quaint, neat, and long-standing history – there is just one problem: it is not true.

From time to time, the author, a descendant of the founding families, and whose passion runs deep for early Greenwich history, would run into Missy Wolfe in the town hall record vault. There she was taking pictures of each page of the oldest record books and transcribing and preparing a new citation ordering system for each document. She has now digitally transcribed literally every page of the first 100 years of the town’s handwritten Commonplace and Land Record books. These have become the Town’s most authentic original source documents, in addition to records of an even earlier time that are housed within Dutch New York archives in Albany, New York (it will be remembered that Greenwich spent nearly the first two decades of its settlement as a Manor under Dutch jurisdiction).

What becomes clear in comparing the summary of Wolfe’s transcriptions in Hidden History of Colonial Greenwich, with long standing beliefs as written by S.P. Mead is that there are many differences between them. This is not the fault of Mead’s analysis but of the technology of his time. The sheer

volume of the archives of the town for its first one-hundred years, surpassed his ability to see and sort the many thousands of town documents comprehensively. He did his job with the tools he had, and it has been a greatly useful and cherished book for over one century. But new technology has enabled fuller reporting and now the past can be more clearly seen.

It is learned from Wolfe’s work the under-reported saga of attempts to tame the Mianus to serve the first settlers. The old bridge that was built in 1687 was not built by the brothers Lockwood but by Gershom Lockwood and William Rundle, and the water level there at the time was only two or three

feet deep. The same year in which this first bridge at Palmer Hill Road was built the Town engaged a miller. Wolfe finds:

In 1687, the town contracted with Jonathan Whelply to make and maintain a “corn” mill, which meant grinding both wheat and Indian corn. He was given twenty acres of land on the west side of the river and fifteen acres on the east side, above the Country Road, plus ten acres in the “Cranberry Meadows,” in North Mianus as planting fields to support the mill. Whelply obliged himself “to grind for the 14th part both of wheat and Indian [corn] and other grain which shall be brought to said mill.” The town also contracted Whelply to build and operate a sawmill.

With Whelply chosen by the town in 1687 to perform his charge to build the corn mill, something happened – six weeks later the Town sought out Joshua Hoyt of Stamford to be perform the same task originally given to Whelply. It appeared Whelply reneged. The Town made sure to set the rules and prices for Greenwich men to use the mill, versus non-Greenwich men – especially because they were asking a Stamford man to operate their Greenwich mill. One thing that early Yankee farming communities have consistently demonstrated, is that they took great pains to meticulously set out agrarian policies and were by nature extremely suspicious and jealous men of one another (especially between Stamford and Greenwich as demonstrated by their early ecclesiastical relationship). Joshua Hoyt was asked to make the mill operational by 1689 and was successful in achieving that deadline.

Then suddenly, Joshua Hoyt died. The operations of the mill weretaken over by Joshua Webb, John Wescut (Wescott), and Zachariah Roberts, while the Town sued Jonathan Whelply. The colony court found against Whelply and he was fined £40 and imprisoned – but not all ended badly. Whelply was

later released from prison and made amends with the Town, for as Wolfe writes:

In 1695, the town again “became sensible to the great necessity for a horse bridge over the Mianus River for the convenient and safe passing over of people and their horse or feet upon their occasions.” Jonathan Whelply presented himself for building the bridge, “sensible and sufficient and…suitable passage for horse to pass over with two bushels of corn on his back without hazard or damage by the rails of said bridge.”

Whelply was paid for his work with one bushel of Indian corn for every head of household in the tax lists of 1695. Wolfe continues, that the town would give Whelply:

‘the help of a team of two oxen, one horse and a man for ten days for his improvement in said work.’

Today, where the old mill once stood and on the lands beyond, the Millers Crossing condominium complex now stands – the name of the complex is not accidental.

In 1713 the Town required a replacement bridge from the one Whelply had constructed nearly twenty years prior – the bridge was a main thoroughfare to Stamford and beyond and had suffered greatly from

its rough frontier wear and tear. Our newly available record summary shows that funding of the construction of a replacement bridge at Palmer Hill was requested from one Colonel Caleb Heathcote of Scarsdale. Wealthy Heathcote was near his last term as Mayor of New York City and was the Judge of the Court of Admiralty for the Provinces of New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut. He was one of the Nine Partners of the 1697 patent to Duchess County, and he became an extremely influential power broker, and regional land speculator. The oldest town records show many Greenwich townsmen selling their Cos Cob tracts to Heathcote including one of the author’s ancestors, Joseph Finch, Jr. Healthcote’s financial support for a replacement bridge at Palmer Hill Road unfortunately never happened. The mill at Mianus was also in need of replacement and in 1716 a new one was built with unknown funding – and thus the second bridge and mill stood for some four to five decades until 1748. It was in this year that the Town ordered a second mill elsewhere to be built. As Wolfe writes:

In 1748, a second Mianus Bridge and dam was built in a more southerly location – by the weir, by the modern Boston Post Road crossing. The town, “have by a vote given Joseph Purdy liberty to beg for money to build a bridge over by the weir [and]…Josiah Reynolds to repair. Further town by vote make choice of Josiah Reynolds for to cull stones and James Rozman to cull stones.” This became known as Purdy’s Bridge.

This new bridge put the one at Steep Hollow in a secondary position, as well as its mill. For new mills were springing up all over and it was no longer the only operation in town. There were more options as the First Society expanded into the lands west of the Mianus River, forming the Second Society or West Society, versus the East Society. Things were changing, things were developing and growing – that is until tragedy struck. A proceeding from the records of the First Congregational Church (Old Greenwich – the First Society) states:

“September 19th day 1787 the greatest flood that was ever known since the memory of man swept away Titus and Mianus mill and all ye bridges.”

So no – the old 1687 bridge was not rebuilt into the new one in 1907. Indeed, the old bridge was gone – more particularly the second bridge was gone. As Missy goes on to write:

One month later, four Titus men were granted rights to rebuild a mill on the Mianus (at the Post Road crossing), with some caveats:

- That Purdey’s stone dam be used again as a foundation.

- That two docks be built on each shore of the river.

- That a flood gate in the form of a field gate be built into the dam.

- A crane must be erected to swing boats over the dam.

- A bridge, wide enough for horse-drawn carts must be built.

- A small boat called a scow must be provided for public use in the mill pond or reservoir north of the dam.

- All work must be completed within four years.

This work was accomplished, and in 1796 Peter A. Burtus and Company took title and enlarged the docks.

The old bridges were gone. The one featured in the photo of the 1907 article may have been built between 1787 and 1796…about one hundred years after the traditional narrative in the Mead history books. Yet, this is unlikely due to the invention of the railroad in the mid-nineteenth century. The current dam at the Mianus River today, next to the Adult Day Care Center, is the legacy of the dam that was constructed to supply water for the power plant for the early railroad companies (there were early designs to have a railroad track run to Ridgefield and the railroad companies purchased land all over Cos Cob for this purpose, but the concept never came to fruition). This raised the water level of the river some sixteen feet – thus the new bridges constructed in the late 18 th century also were dismantled and had to be constructed once again.

So did Old Palmer witness Washington cross over the new bridge at Palmer’s Hill after the horrific floodof 1787? Yes. Was it the same bridge dismantled and repurposed to build the new one in 1907? No.

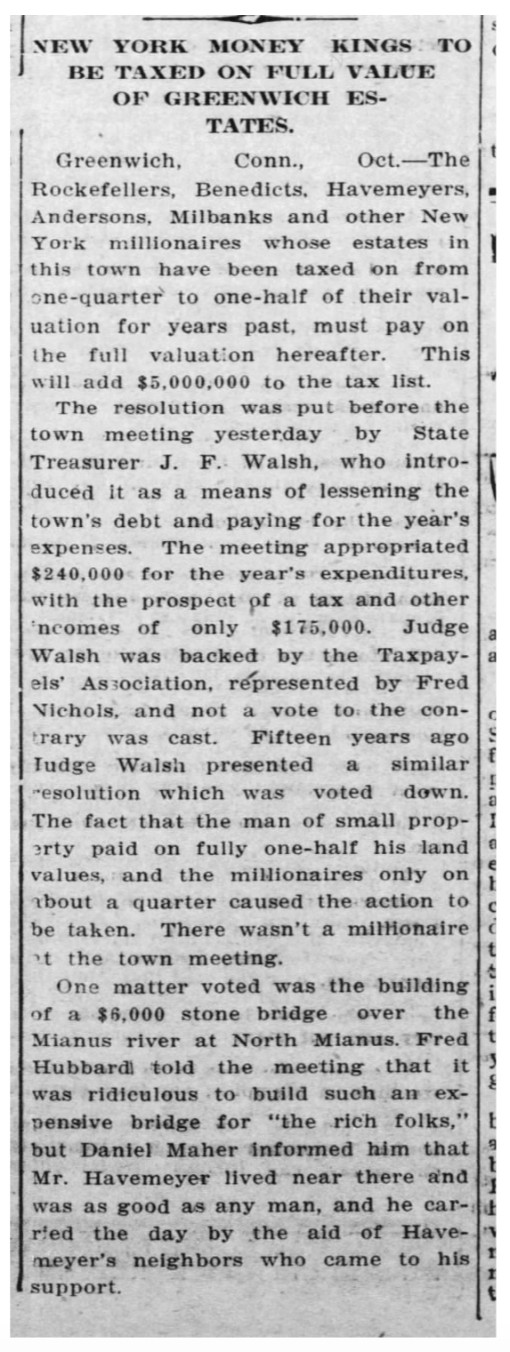

The author believes the Palmer Hill Road bridge featured in the photo from the 1907 article was the bridge discussed in a newspaper clipping provided below. It is a 1906 newspaper article from The Natchez Democrat that was sent to the author by Missy Wolfe who shares the same historical interests.

They chuckled that some local attitudes have also had a long history. Griping about the 1906 costs for rebuilding the Palmer Hill Road Bridge, conciliations between the haves and have nots in Greenwich have been debated long term. Most residents will recognize many of the names in the article as names of streets throughout town today – but they used to be actual people and families. These people were the Bezos, Gates, and Musks of their day. People wanted to read about them, even in Mississippi. Many of them just happened to have estates in Greenwich. The article reads:

NEW YORK MONEY KINDS TO BE TAXED ON FULL VALUE OF GREENWICH ESTATES

Greenwich, Conn., Oct – The Rockefellers, Benedicts, Havemeyers, Andersons, Milbanks and other New York millionaires whose estates in this town have been taxed on from one-quarter to one-half of their valuation for years past, must pay on the full valuation hereafter. This will add $5,000,000 to the tax list.

The resolution was put before the town meeting yesterday by State Treasurer J.F. Walsh, who introduced it as a means of lessening the town’s debt and paying for the year’s expenses. The meeting appropriated $240,000 for year’s expenditures, with the prospect of a tax and other incomes of only $175,000. Judge Walsh was backed by the Taxpayer’s Association, represented by Fred Nichols, and not a vote to the contrary was cast. Fifteen years ago Judge Walsh presented a similar resolution which was voted down. The fact that the man of small property paid on fully one-half his land values, and the millionaires only on about a quarter caused the action to be taken. There wasn’t a millionaire at the town meeting.

One matter voted was the building a $6,000 stone bridge over the Mianus river at North Mianus. Fred Hubbard told the meeting that it was ridiculous to build such an expensive bridge for “the rich folks,” but Daniel Maher informed him that Mr. Havemeyer lived near there and was as good as any man, and he carried the day by the aid of Havemeyer’s neighbors who came to his support.

And here is another example of those beloved Johnny-Come-Lately’s, those dear New Yorkers getting their way in Greenwich once again. It also shows that expectations and daily life were different. The assessments were lagging and highly undervalued – and where the wealthy New Yorkers wanted to develop and bolster property in town, both public and private – the sons and daughters of Greenwich were cautious, not just financially but also concerning their history. Their history was not just something in a book on Strickland Road, this was a history from which they inherited in land, bone, and blood. It was personal.

What is in a name? Quite a lot of folklore, history, and hidden history. Be careful when reading early history books. They possess useful, accurate and good information – but they are not Gospel. History always requires updating with the work of countless modern researchers and scholars. Missy Wolfe’s work brings us such important new resources. Hidden History of Colonial Greenwich is a summary of our first 100 years; and the Greenwich town archives of the first European century here without narrative will be published in 2021. What is in a name? Centuries of human life here in Greenwich – so similar yet so different from our own. They are full of rules and regulations, kinships, quarrels, homes and hearths;

arguments and jealousies; even fear and epidemics. Like the past, the old bridge, nay the old bridges, are gone – but their story and the people who made them, now serve as the bridge to their early memory and development. And through new modern tools, researchers continue to devote many hours to re-open the books and see history with a clearer vision. The old bridge is gone – but the rich, intricate, and unique story of Greenwich is not.