Donna de Varona is an American former competition swimmer, activist, and television sportscaster.

The global pandemic that reshaped how we function and interact as humans left no corner of the world untouched. Every aspect of our lives changed on the personal level, but the cancellation or disruption of seemingly invincible cultural touchstones like the Olympics served as stunning reminders of the uncertain times we all endured. An event that intertwines and invigorates the world once every four years is needed now more than ever after a period of such isolating international disconnect and despair.

After countless fits and starts threatened to condemn the 2020 Tokyo Olympics as collateral damage of the pandemic, we will soon get to enjoy what the Japanese refer to as the “Recovery Games,” a theme articulated in observance of Japan’s upending earthquakes, floods and natural disasters including the devastation of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster when on March 11, 2011, when 18,000 Japanese lost their lives.

Long before the Games’ hard-fought return to Tokyo after 57 years, I cannot help but reflect on the history of the Olympics in the Land of the Rising Sun. More pointedly, with a renewed focus I recall how profoundly participating in the 1960 Rome Olympics and especially those in Tokyo impacted my life and those of my teammates. Indeed, 2020 is not the first time an Olympics in Japan has been rescheduled. Eighty years before the pandemic disrupted the impending 2020 Tokyo Games, Japan was set to welcome the world of sport to its shores in 1940 for the Summer Games.

In fact, my Dad, David de Varona, had hoped to qualify for those Olympics as a member of the fastest eights rowing crew in the nation. Then a senior at the University of California, Dad had his eyes set on reaching the world’s brightest athletic stage and representing our country.

Indeed, 2020 is not the first time an Olympics in Japan has been rescheduled. Eighty years before the pandemic disrupted the impending 2020 Tokyo Games, Japan was set to welcome the world of sport to its shores in 1940 for the Summer Games. In fact, my Dad, David de Varona, had hoped to qualify for those Olympics as a member of the

fastest eights rowing crew in the nation. Then a senior at the University of California, Dad had his eyes set on reaching the world’s brightest athletic stage and representing our country.

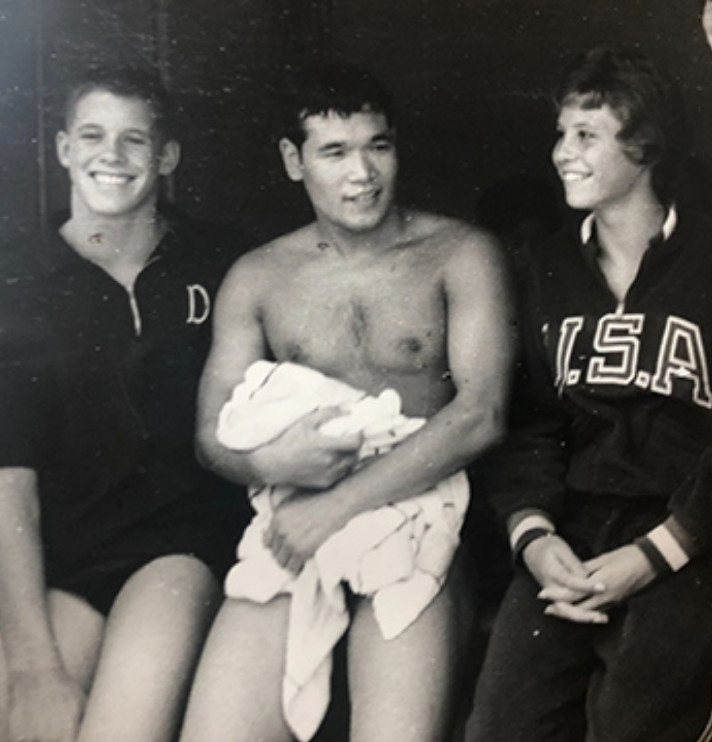

medalist in 1960 Yoshihiko Yamanaka of Japan. Contributed photo

Unfortunately, a deadly global crisis that sunk the world into a state of upheaval also struck unexpectedly, as World War II derailed the 1940 Olympics. Young, ascendant athletes just like Dad from all over the world saw their dreams dashed. Proving that history doesn’t necessarily repeat itself but instead rhymes, many of the potential competitors in the 2020 Tokyo Games have been given a lifeline to glory with the rescheduling of the event. This stands in stark contrast to the alternative aspiring Olympians like Dad faced in lieu of competing in the athletic arena. Instead, the outbreak of war thrust most if not all young Olympians into representing their countries on a different kind of playing field.

My dad, for example, traded in a shot at gold for a role with the Red Cross. He relied on his athleticism to fight his way up to the front lines to help America’s soldiers in need. After the close of the war, Dad was recognized for his courage as the only field director to jump with paratroopers 11 times in combat. Little did he know that only a few decades later, he would find himself back in Tokyo in what once was enemy territory, realizing his Olympic aspirations through me.

My first trip to Japan came one year after I participated in the 1960 Rome Olympics. Swimming for Team USA as a 13-year-old, I held the world record in the 400 Meter Individual Medley. Regrettably, my world-best event in 1960 was not on the Rome Olympic swimming schedule so instead, I focused on the 100-meter freestyle and

qualified for Team USA as a member of the 400 Meter freestyle relay. During the Olympic competition, four of us alternates swam in the preliminaries to conserve energy for our fastest 4 teammates. In turn, they could pour everything into bringing home the gold in the final.

the back of European Life Magazine. Contributed photo

Getting a taste of the world’s highest level of competition in Rome only fueled my drive to invest four more years of hard work to achieve my dreams. Thankfully, the Olympics included the women’s 400 Individual Medley on the program in Tokyo for the first time in history, opening up my door to gold. This unique opportunity alone gave me motivation enough to train relentlessly. As I began to dominate in the pool during the Rome-to-Tokyo interregnum, the payoff of being a teenage world record holder finally came. One year later, I joined three other age group swimming prodigies to tour Japan.

The Japanese swimming federation and the Olympic Games organizing committee wanted to inspire its youth as well as promote the Olympics. We were the ambassadors of that message. As is often the case with host cities, many in Japan were concerned about the costs and wisdom of staging the 1964 Olympics. We canvassed the country and participated in exhibitions promoting the Olympic spirit and demonstrating the unique benefits of welcoming the world back to a modern Japan. On one very memorable occasion, we gave a clinic in a remote Japanese farming village. The hamlet ‘s prize was an outdoor pool, which was snugly nestled in the middle of a rice

paddy. We took part in motivational talks, press conferences, and formal dinners. Furthermore, we observed roads, hotels, and all kinds of infrastructure being built no matter where our barnstorming tour stopped next. To wit, Japan was on a frenzied sprint to finish up its rail lines to carry spectators and tourists from Tokyo to Osaka on its state-of-the-art bullet train.

The Japanese government sought to prove to the world that Japan was back and better than ever. The 1964 Games would be a veritable coming out party for the island nation, a reintroduction to democratic world affairs and commerce after the devastation of morale and infrastructure the country endured during World War II.

I returned to Japan for a friendly competition one more time before taking part in the Opening Ceremony of the 1964 Olympics. With the inspiration of hosting the Olympics, the country had transformed itself remarkably while maintaining its rich and elegant cultural traditions. I truly felt as if I was welcomed back to Japan by the locals as a

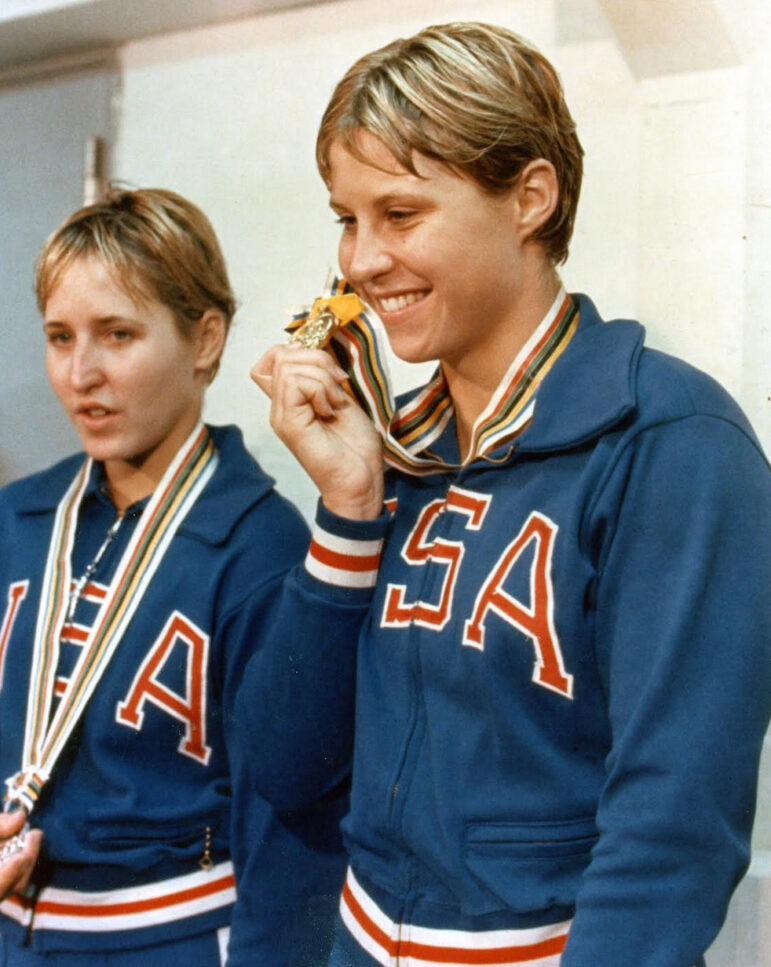

daughter. Feeling like I was adopted, it gave me an overwhelming sense of relief and joy when I finally did win a gold medal in the 400 Meter IM in a rewarding clean sweep for team USA with Sharon Finneran second and Martha Randall third. In a well-deserved karmic payoff, I once again took part in the 400 free relay but swam the final

instead. I came full circle from my Rome experience and helped Team USA shatter the world record while winning gold in the event.

I also know that the real treasures of taking part in the Olympics are the lifelong friendships I made in the Olympic Village, during the Opening ceremonies, and later as a broadcaster, activist, and volunteer. In Rome my seminal moment came when without a world basketball great Walt Bellamy reached down to lift me high up on his shoulder

so I could witness the torch bearer’s entry into the Olympic stadium! I scored an autograph from Muhammad Ali—and made lifelong friends with sprinter triple gold medalist Wilma Rudolf and her teammates. During the Tokyo Olympics I made another significant connection with a German rower named Jurgen Schroeder. During the 1964 Opening Ceremony, he draped his raincoat over my shoulders to shield me from a misty rain. Echoing the spirit of rebirth in 1964, Jurgen drew on his inspirational Tokyo experience and worked tirelessly to help bring the 1972 Olympics to Munich, Germany. To this day, he works on behalf of athletes. In the cafeteria line, I met and befriended future Knick’s star and U.S. Senator Bill Bradley. During his illustrious career in public office, Bill proved to be a go-to leader in all matters dealing with the Olympics, athletes’ rights, and protections for athletic equality. When tragedy stuck on 9/11, my Olympic friends from all over the globe—spanning from Cuba and Russia to South and Central America—reached out immediately. Collectively these anecdotes capture the types of hidden stories that every Olympian cherishes along the way.

Perhaps more than any other reason, this is why I have anchored my life in sport while working to protect and support this worldwide Olympic experiment.

I recall the overwhelming feeling when I walked into the cavernous, enclosed Yoyogi swimming and diving venue. The spaceship-sized arena was unlike anything I had ever experienced. With considerable forethought, the architects designed the facility so the pool could be converted to an ice rink for winter months skating. For the first time in history, finish line touchpads were installed to modernize and improve the competition in the pool. Moreover, the Japanese acumen in planning, marketing, and delivering those Games elevated the staging of the Olympics as a whole to a new and more sophisticated level. All in all, Japan has hosted 3 Olympics—two winters, one summer,this 2020 edition.

With the Tokyo Olympics underway, my thoughts are not solely focused on medals and world records but rather the unique impact the Tokyo Games may have on modern history. The global pandemic has tested every one of us. It has forced us to be creative, to problem solve, to work together under incredible pressure, to overcome fear and face down a treacherous and invisible enemy. The world feels smaller and more isolated than ever. Nevertheless, we discovered new ways to communicate, form global teams, and take on the many challenges facing us all these last 18 months.

In the world of sport, we have witnessed how a global community has charted an exceedingly turbulent course to keep the Olympics on track for this summer and avoided resorting to an outright cancellation of the event. Luckily, we have not had to blaze the trails last seen 40 years ago in advance of the 1980 Moscow Games. Current IOC President Thomas Bach was denied a chance to compete during the President Carter-lead boycott of those Games. Bach more than anyone knows the price of a lost Olympic Games opportunity. Under his leadership, the dedicated stewards of the Olympic movement have worked overtime to ensure the Olympic flame burns brightly

amidst the darkness of a pandemic. It has been costly on so many levels, but the payoff of the hard work is about to come due.

On personal and public levels, now more than ever we all need inspiration. We yearn for believing that things can get back to normal and want to trust in a broad scope vision of how to handle global crises. As in 1964 when Japan stepped up to take the risk of staging the games, Tokyo 2021 also has a critical role to play in looking to the future again with hope.

Within my own personal story, I have often wondered what my Dad and Mom felt when they were so warmly greeted upon arriving in Japan and welcomed into the home of a Japanese family. Less than two decades after a fierce war with the people of this same nation, harmony and understanding was being forged once again. Only the staging of the Olympic games in Tokyo would have provided my parents with an opportunity to meet and find common ground with their hosts. The time they spent together to celebrate the Olympics was a gift. An unadulterated time to heal after their shared experiences of dealing with the hardships of the war.

The Olympic Games and its movement hold out a lofty vision. For all its critics as well as those who want to exploit this platform in service of either political or personal agendas, this Olympic ideal continues to inspire a global community of 206 nations. As the athletes in Tokyo continue to take to the field of competition, they will provide visible affirmation that the three values of Olympism – excellence, respect, and friendship – are true motivators for a world seeking common ground.

Today I look with great anticipation and respect to Japan honoring the original theme of 2020 by declaring these Olympics as the “Recovery Games.” Anticipation for what’s to come, both in the weeks of competition ahead as well as on the post-pandemic horizon. Respect for a resilient global community determined to work together to fight for and embrace what is truly possible.

There is no doubt the Republicans and Democrats of U.S. politics are often against each other. The current president, Joe Biden, is facing some displeasure from the southern side, including the college football team.

Sports have evolved over the years, including its conversation. These days, we have sports rivals and political opponents that speak rashly against each other. Sports being a gathering of people with diverse opinions but a common goal on the field accommodates this more than several other sectors.

The same college gossip that happened during President Trump’s tenure is currently happening with President Joe Biden.

liontips has further information on the latest sports news.