First in the Sustainability Committee’s One Land Series on Biodiversity.

By Sarah Coccaro, Town of Greenwich Conservation Resource Manager, Conservation Commission

The Lawn Paradigm

Our nation’s obsession with lawns is evident by the nearly 40 million square miles of lawn in America, making grass the largest irrigated crop in the U.S. It’s not a crop that anyone can eat; but it nevertheless consumes vast amounts of water resources and fossil fuel inputs by way of gasoline-powered lawn equipment, fertilizers, pesticides and weed killers, outstripping fossil fuel use of any agricultural crop.

Grasses live a completely unnatural life cycle. We don’t let grass grow tall enough to go to seed, we water and fertilize it to keep it from going dormant, and we don’t let it die or reproduce. Lawns are sterile and expensive, and some regard them as boring in their uniformity- but they are a hallmark of homeownership. So why do we care so much?

Today, there is a significant industry that exists around lawn care and management. From equipment to chemicals to seed, aeration and water schedules, lawns require resources, knowledge, time, and money. The sheer volume of resources required to keep lawns alive is staggering, such as requiring the equivalent of 200 gallons of drinking water per person per day.

We are at a moment when the American Dream, inasmuch as it still exists, is changing. With a growing movement that embraces a more natural lifestyle, there is a trend toward a more diverse entomological system. With the growing awareness of the climate crisis a movement towards a more sustainable and regenerative approach to the landscape has been emerging.

For Nature, Lawns Offer Little

For all the cost and care that goes into the perfect lawn, grass turf does not provide any of the services our landscapes must offer to offset the huge demands humans place on that landscape. Lawns don’t sequester carbon, manage the watershed, support a food web and pollinators, prevent erosion and flooding, or oxygenate our air. Their maintenance produces more greenhouse gasses than they absorb, and they are ecological dead zones that contribute to the die-off of insect populations.

Next time you walk in your neighborhood, take a wildlife census of the yards you pass. What you’ll invariably find is that the pristine lawns have almost no wildlife – no bees or butterflies, no beetles, no grasshoppers or crickets, no lacewings, no spiders, no roly-polys. And if there are no insects, there are also no songbirds, no bats, no frogs or toads. A staggering 96 percent of songbirds, even those that subsist on seeds and berries as adults, rely on insects to feed their young. If you look at North American birds, insect or amphibian populations, all are in decline. And our lawns aren’t helping.

Alternatives to lawn

Ironically, lawns are the low-hanging fruit many of us can correct. There is a myriad of options to replace lawns that don’t involve fertilizers, watering, mowing and blowing, saving time, money and noise. Cities and municipalities across the country have enacted rebate programs to replace lawns with flowering plants and even paying families and homeowner associations to design gardens that collect storm water in water features and underground rain barrels. Such policies can lead to big changes.

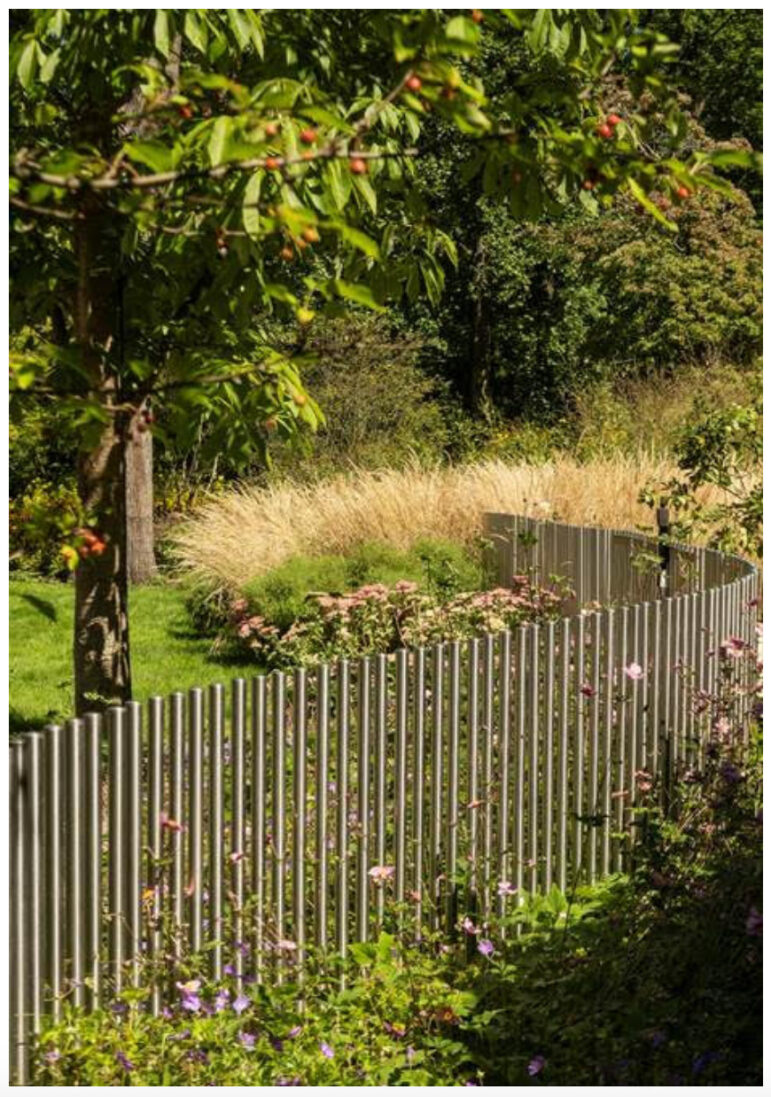

Consider a different kind of landscape. Natural landscapes, “eco-friendly” or permaculture-style landscapes mimic natural systems, embrace biodiversity, and do not require chemical inputs of the tightly manicured suburban lawn model. Still want low-maintenance ground cover? Consider moss, sedum, creeping thyme, or clover as an alternative. Ask yourself if you need all that lawn. Reduce grass turf areas by adding a pollinator strip or perimeter garden to your lawn. Do you have a large lawn area? Convert lawn to meadow or prairie, or that vegetable garden you’ve always wanted.

A healthy home-scape is interwoven with native trees, shrubs, plants and water and even a small portion of grass that can increase biodiversity, help to flatten temperature extremes and restore our landscape for all our animal neighbors. Plus, it can be beautiful. The interconnectedness of less lawns, healthy home-scapes, preserving trees, increasing biodiversity, all help mitigate the effects of climate change and help keep our community abuzz and biodiverse.

For more information on how to plant healthy yards, visit our partner’s websites: Greenwich Pollinator Pathways, Greenwich Land Trust or Healthy Yards Westchester.

Look for the second article in the One Land series, “The Alien Invaders in Our Own Backyards: How invasive plants are taking over our native landscape” next Thursday.