Siegrun Pottgen lived in her historic Victorian house on Glenville Street for decades.

Siegrun Pottgen outside her Queen Anne style house at 9 Glenville Street, which dates back to 1898. Photo: Leslie Yager

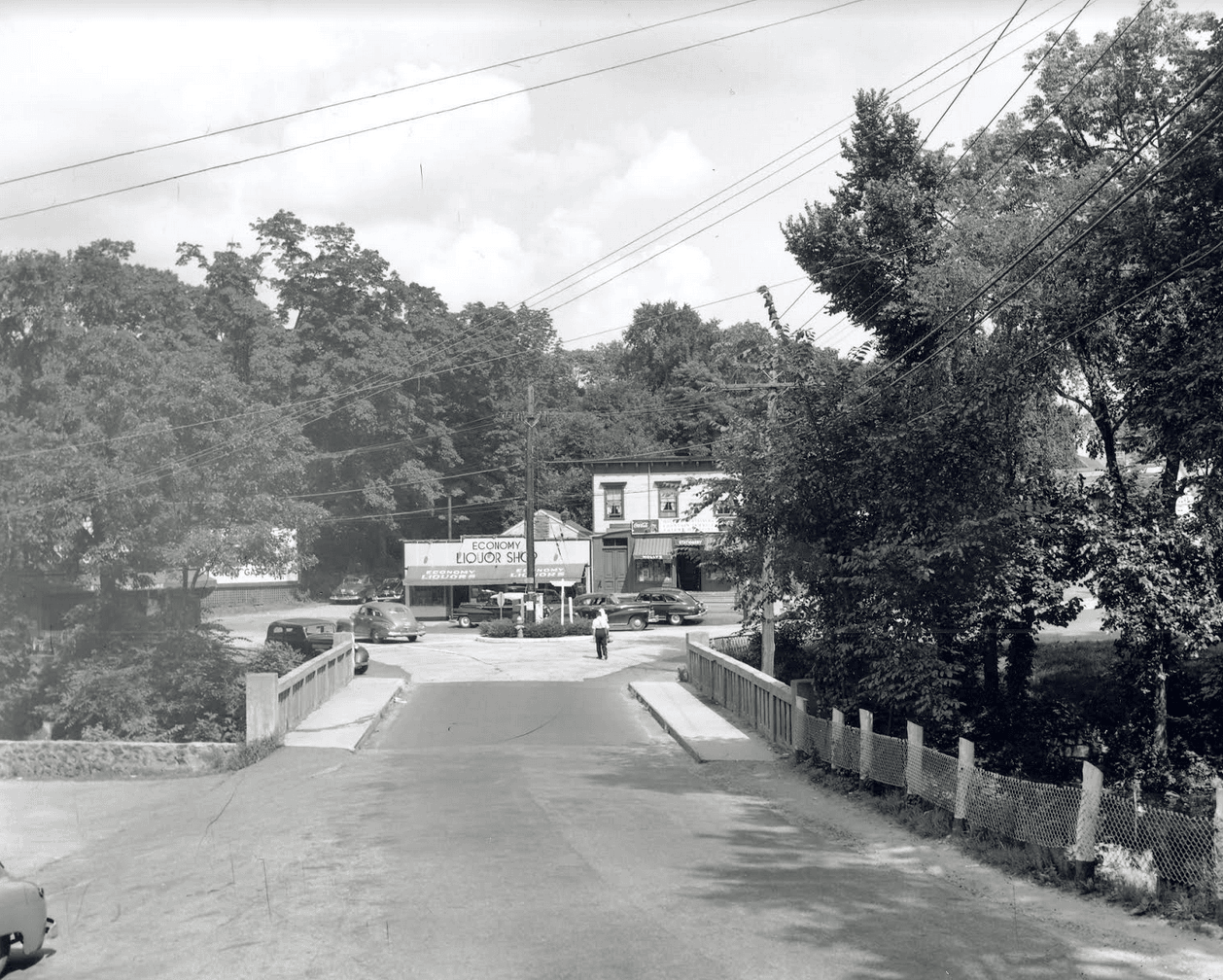

An undated photo courtesy of the Greenwich Historical Society shows a traffic circle at the intersection of Riversville Rd and Glenville Street. The white Pottgen house is in background.

Andy’s Filling Station on the Pottgen property at 9 Glenville Street. Photo courtesy Greenwich Historical Society

She married into the Pottgen family in 1962 and moved with her husband Charles to 9 Glenville Street in 1963. As a stay-at-home mother raising three children, she waited until her youngest, Monika, was a junior in high school before launching a career in public service, including work as both a State Marshal and as an elected Greenwich Town Constable for 33 years, a position she holds today.

“My husband’s idea was you take care of the house and the kids,” she said during a recent interview in her tidy kitchen.

“But I was itching to get out and do my enforcement,” she added, describing her first paid employment as the time she “busted loose.”

“I went over his head,” she said of her husband. “I wanted to be my true self.”

Built in 1898, the Pottgen house is a Queen Anne style Victorian, with a place on the National Historic Register. It replaced the original 1858 house, which served for a time as a boarding house for felt workers. Sadly the original house burned down in a fire in roughly 1897.

From her perch at the corner of Angelus Drive and Glenville Street, Mrs. Pottgen has witnessed the transformation of her neighborhood, including the conversion of the American Felt Company’s felt mill to a retail and office complex in 1978.

Gone are the days of changing colors of the Byram River, reflecting the color of the felt dye on a particular day, and workers walking home for lunch.

“The felt mill moved to Newburgh,” Pottgen said, adding that she remembered the fumes from the soil around the river. “They removed the contaminated soil in big construction trucks, one after the other.”

Sign up for the free Greenwich Free Press newsletter

Sign up for the free Greenwich Free Press newsletter

Of the office complex that replaced the felt mill, what was forward thinking in the late 70s has run its course, and Pottgen has seen those offices drain of tenants and a new plan approved by the Town to convert them to residential apartments.

She has also seen the construction of not one, but two new Glenville Schools on Riversville Rd, the opening of Vinny’s Pizza on the dangerous hairpin turn across from the now Bendheim Greenwich Civic Center (the 1920 Glenville School), and witnessed a steady increase of traffic along the Glenville corridor where traffic from I-684, Westchester Airport, the Merritt Parkway and private schools moves down King Street, and past her historic house on the route to central Greenwich.

A&P at the corner of Glenville Street and Riversville Rd. Courtesy Greenwich Historical Society

View of bridge over Byram River from the east to the intersection of Riversville Rd and Glenville Street. Photo courtesy Greenwich Historical Society

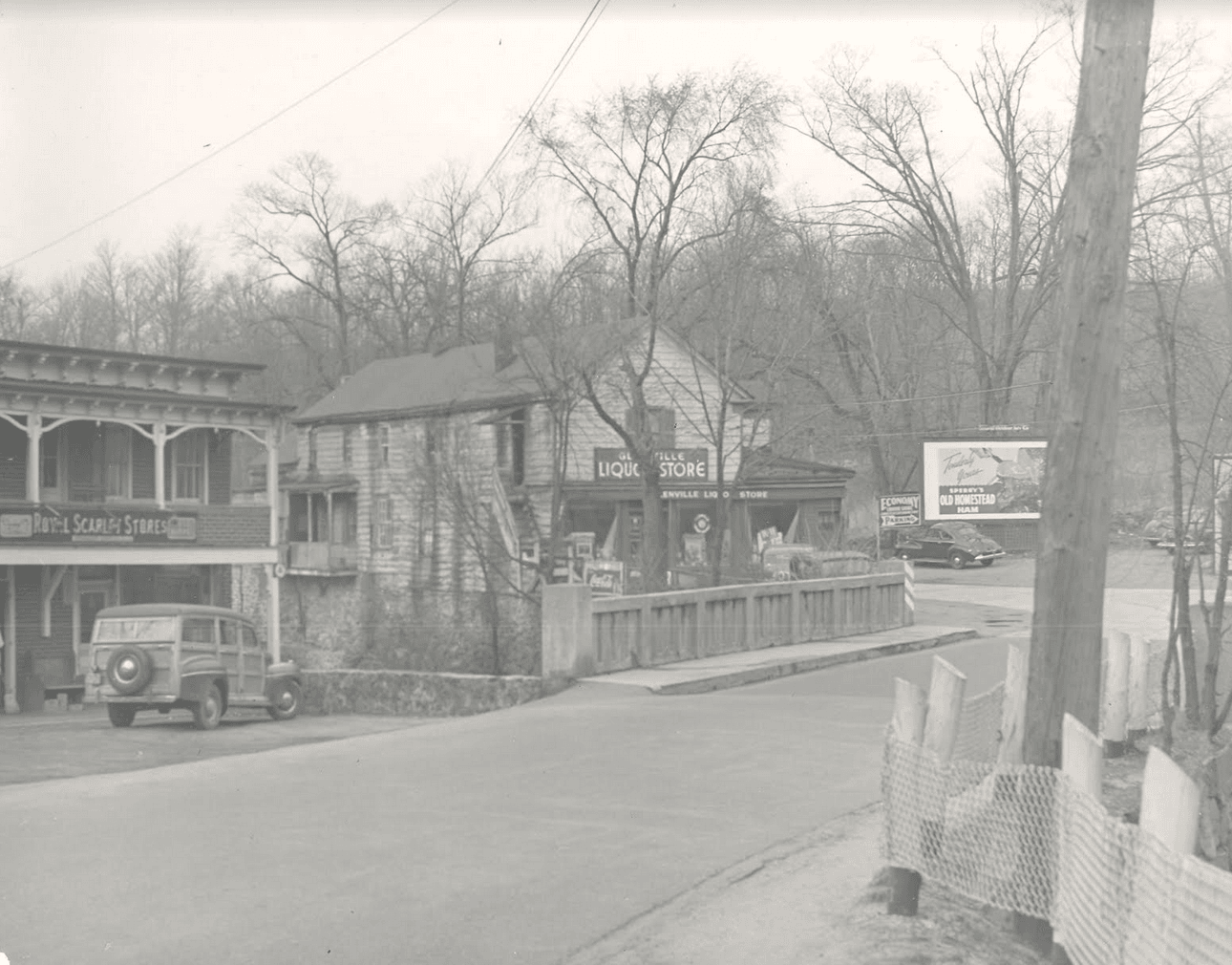

Looking east over the bridge over the Byram River in Glenville. Watson’s Catering is now located at the site of the building to the left. Photo courtesy Greenwich Historical Society

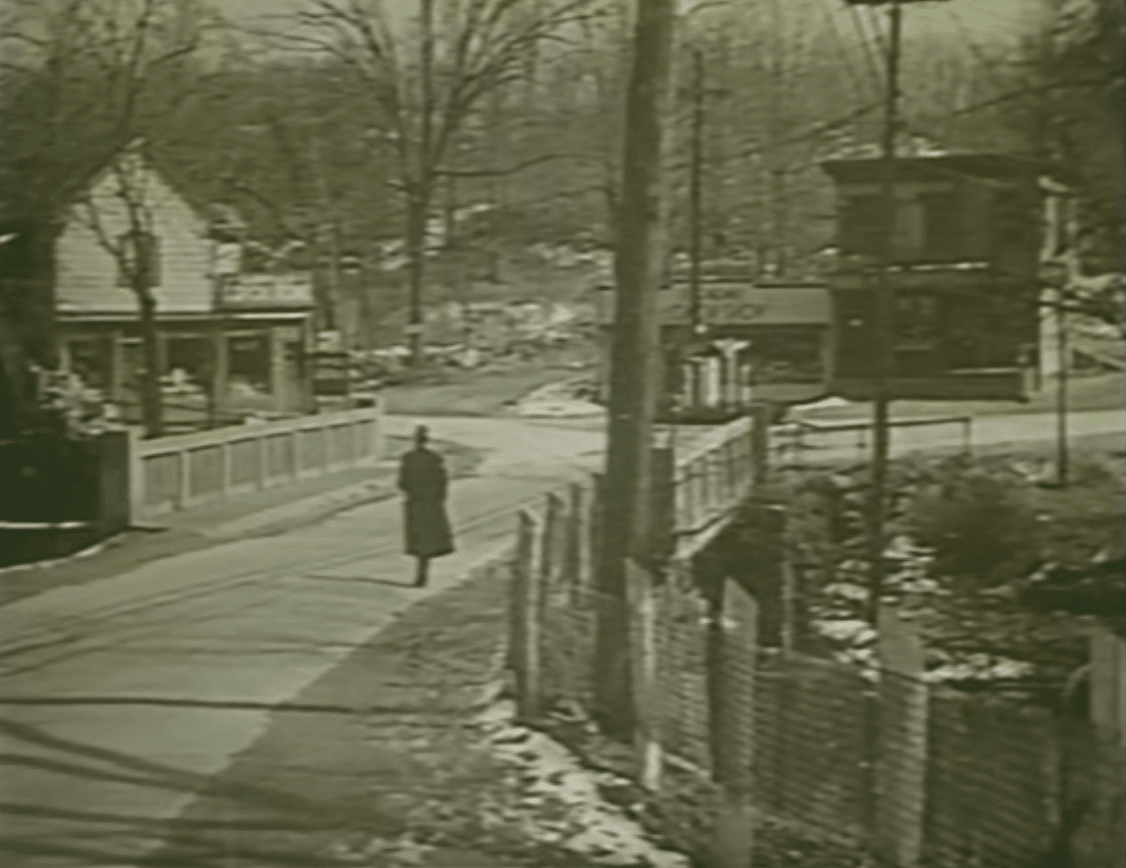

Undated photo of man walking down across the bridge facing along Glenville Street. Photo courtesy Greenwich Historical Society

Glenville Liquor Store. Photo courtesy Greenwich Historical Society

Glenville Post Office near current intersection of Glenville Street and Glen Ridge. Photo courtesy Greenwich Historical Society

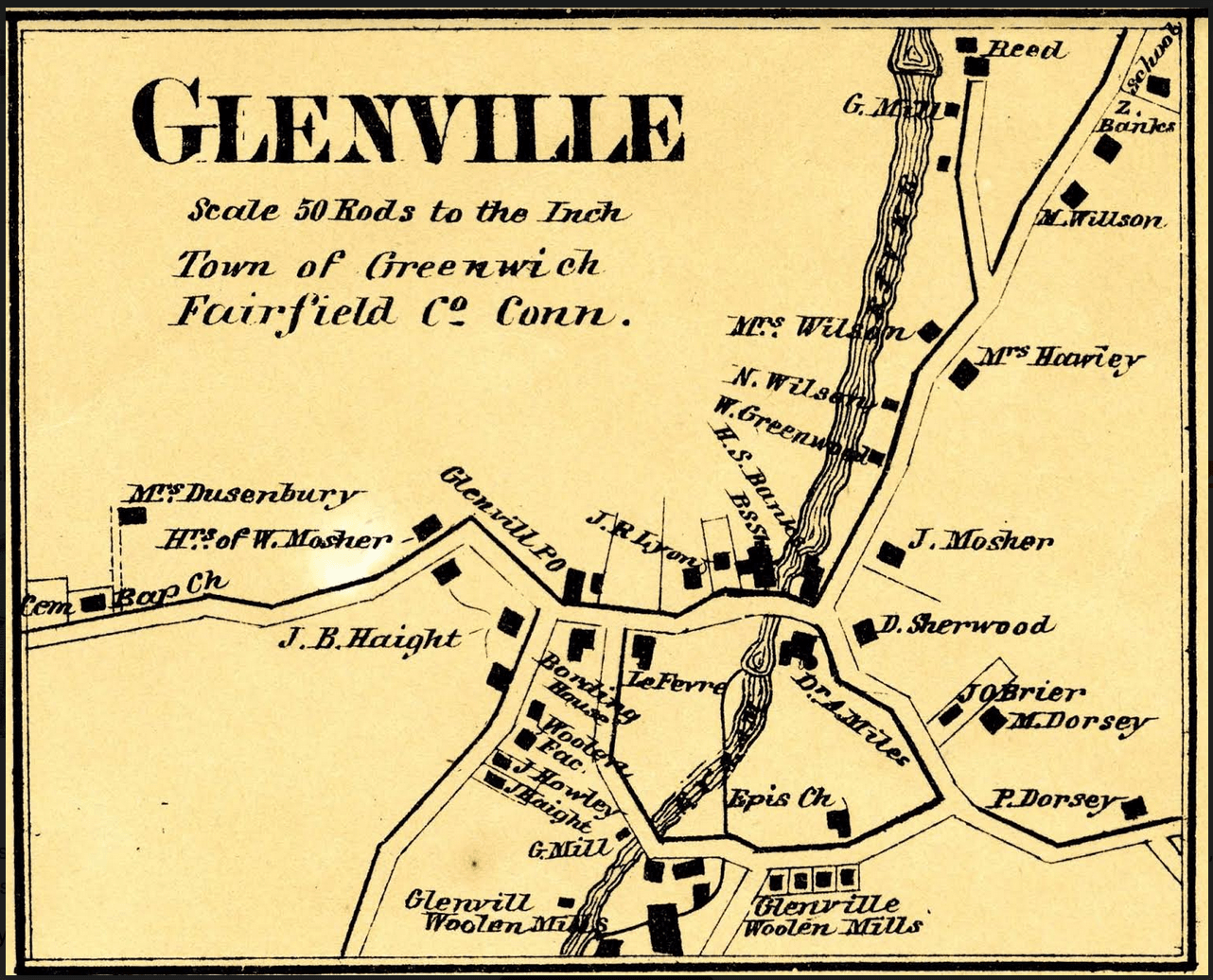

Map of Glenville dates 1867, courtesy Greenwich Historical Society

As a woman in law enforcement in the early 1980s, Mrs. Pottgen was ahead of her time.

“My husband didn’t want me to work,” she recalled. But she picked her moment, and beginning in 1982 she became a Deputy Sheriff, though the job was later reclassified as State Marshal in 2000.

“There were two women Marshals out of 45,” she recalled. “I was the third.”

As someone who bristles at injustice, she described herself as “an enforcer at heart.”

“I was asked by the High Sheriff of Fairfield County to be a State Marshal because I had an interest in policing,” she recalled. “I grew up with a military background.”

From 1980 to 1985 she served as a Special Officer with the Greenwich Police Dept.

“You would donate one night a week from 8:00pm to midnight and partner in the police car for the night,” she said. “There were a lot of adventures there and I learned a lot about the Town of Greenwich.”

“That was my opportunity,” she said of being a Special Officer. “That led to my being asked by the High Sheriff to be one of his deputies. In 1982 I ran his campaign and he was elected.”

Pottgen was delivering papers the night the Mianus Bridge on I-95 collapsed. “It was small claims, not even a big deal,” she recalled of the papers. “But I had to get to that person at night.”

“We are independent contractors. Attorneys hire and pay us to serve papers. There is no salary,” she explained. “And private people hire us for small claims. You need a marshal to serve your papers or it’s not legal.”

“You are a court officer and you have the power of arrest,” she said of the job of State Marshal. “I arrested someone once. It wasn’t a big deal; they went quietly. The restraining orders are where the danger lies.”

In addition to being a State Marshal, Pottgen served concurrently as a Republican Town Constable, an elected position she holds today.

In fact, having first been elected Constable in 1985, she is the longest serving Town official in Greenwich.

Pottgen said the job of Constable is similar to being a State Marshal. “You’re an officer of the court, the difference is you are elected by the people. The Deputy Sheriff is appointed.”

As far as memorable work experiences, Pottgen said not once, but twice, a man opened the door with no clothes on. “My eyes never wavered,” she recalled.

Pottgen also remembered a time she had to think on her feet as she attempted to deliver papers to a man in a back country mansion.

“It was a very exclusive, big mansion with the heaviest big wooden door I’ve ever seen. I was there in the early evening and the guy opens the door I said, ‘I’m Marshal Pottgen and this is for you. It’s a summons to court.’ And he takes the door and slammed it in my face and I had just enough time to pull my hand back.”

Pottgen said her approach has been to always treat people the way she would want to be treated – with respect.

“What’s saved me over the years is I have no attitude. I don’t come on strong. I’d step back and say, ‘Oh, okay then. Plan B is coming up.’ I’d never tell them what that meant. It had them them guessing, and I’d leave.”

She recalled serving divorce papers to a famous basketball player in the lobby of Stamford Superior Court.

“He said, ‘I’m not taking it.’ The cameras were rolling. And I said, ‘That’s okay.’ I touched him and dropped it at his feet and said, ‘You’ve been served,’ and walked away.”

Pottgen said the rule for serving papers was that as long as the paper touched the recipient, she could drop them and walk away.

“He was served,” she said. “This is why I walked away smiling. A little crowd had gathered because he was recognizable.”

Pottgen said in addition to going to court or to people’s homes, she served papers in bars and businesses, and even once waited in a train station during a snow storm to serve papers. “It’s all part of the job.”

She said she also learned to get through security gates and how to serve papers to someone hiding behind a secretary or someone who fronts for them.

“You show your badge and say, ‘I am a court officer and these court papers are for the CEO, not the company,'” she said, adding that usually she’d be escorted straight into the CEO’s office to serve the papers. “I was very subtle, but firm.”

As for transitioning from stay-at-home mother to the workforce, she said, “I’d go out at night when they were already in bed. And I was home when they got home.”

Mrs. Pottgen said her days in Greenwich are numbered, as she plans to move to Indiana and has put the house at 9 Glenville Street on the market.

She recalled how for decades the five bedroom house was bursting with extended family. In fact when she married Charles, they lived with his parents, his sister and his mother’s brother in the house.

“In the old days, you took care of family, and it was a full house,” she said. “It was really full until my sister-in-law bought her own house,” she said of Charles’ sister Joan Truscello who lives nearby.

“And when Charles grew up in the house, he had his grandparents there too,” she said.

She explained the house was passed from father to son, but that her mother-in-law had living rights. “The son inherited it,” she explained. “That was the old fashioned way to handle it – to give living rights to the wife.”

The house at 9 Glenville Street is on .49 acres in the LBR2 Zone. It has 5 bedrooms, an adjacent garage that was once Andy’s Filling station. Photo: Leslie Yager

“Every room has a door,” she noted. “I am proud of this house. I’ve kept it up and have put a lot of money into it.”

Cleaning out the house has been no small task after all the decades of Pottgens residing there.

“The ancestors didn’t have a dump,” she said. “Boy, oh boy, the antiques up there in the attic! Some worth something, some not worth anything. I had to go through it all.”

“There are old photos from the family, but we didn’t know who all of them were. They never smiled in those photos.”

“There were lots of lamps, photographic equipment and viewer slides on glass,” she said, adding that many of the valuable antiques went to United House Wrecking in Stamford.

The Pottgen house, set on .49 acres, in the LBR2 zone, which is business and residential, includes an adjacent garage that once was the family’s gas station. Andy’s Filling Station operated from 1933 to 1954.

Mrs. Pottgen said her husband’s grandfather ran the gas station, and then his father ran it. “My husband closed it down went to California and became an airplane mechanic,” Mrs. Pottgen said. “He went to work for TWA.”

Years ago, Mrs. Pottgen worked with the EPA to take out all the oil tanks from the former filling station. “They opened it opened it up and not a drop spilled,” she recalled proudly, adding that the fee at the time to remove the tanks was $23,000.

The Pottgen house was originally part of a farm, and the property, she said, used to extend all the way to the Byram River in the front, and all the way up Angelus Drive to the rear.

“The family sold it piece by piece during the Depression,” she said.

Though Mrs. Pottgen may be the last of the family to reside in the historic house, she said she never considered it her own.

“I’m very sentimental and was holding down the fort for the family. I never considered it mine, but rather holding it for the family for five generations,” she explained.

And while she won’t miss the heavy Glenville Street traffic, she will miss the Town, the Pottgen house and her career in law enforcement.