Ginger Katz visited Greenwich High School on Thursday to talk about her son, Ian. About 200 students filed into the auditorium and Wellness Teacher Kathy Steiner introduced Katz, who described her son as having had a big heart, which she attributed partly to his sister, Candace, who has Downs Syndrome.

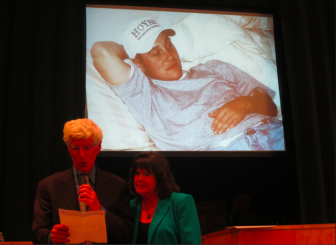

Larry and Ginger Katz. Credit: Leslie Yager

Ian went to Norwalk High School. He went to his prom, had a nice girlfriend and played lacrosse before going on to University of Hartford.

But Ian also had a long battle with drugs before he died of an overdose in 1996 at the age of 20.

“Why do you think kids use drugs?” Katz asked the GHS students.

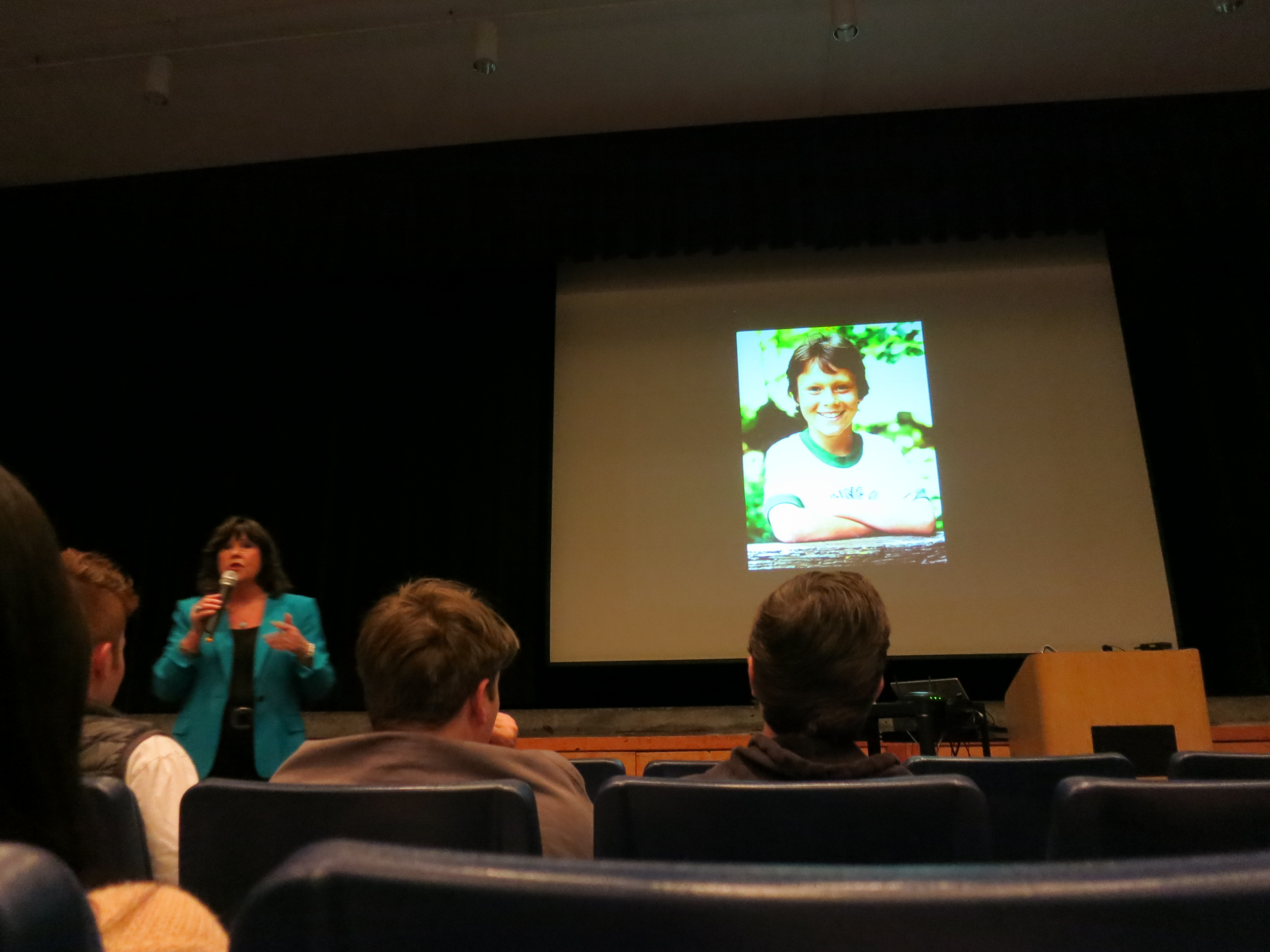

At Greenwich High School Ginger Katz spoke about her son’s death from a heroin overdose. Credit: Leslie Yager

“They’re stressed,” one student said.

“It feels good,” said another.

“Because they’re in pain,” said a third. Other replies included boredom, simple curiosity and peer pressure.

Katz nodded in acknowledgement of each response. She recalled Ian’s comments when he was having to use every five hours in order not to become very ill with what she described as pain twenty times as severe as with the flu, where even the bedsheets are too painful to touch.

“‘Mom, I’m unlucky,’ Ian would say. ‘Mom, I’m messed up. Mom, there is a smorgasbord of drugs at school. If you don’t have money, they give it to you for free.'”

As Katz told the story of Ian’s battle with addiction and ultimately finding him dead in his bed of an accidental heroin and valium overdose, the GHS students listened quietly and filed out at the end of the period almost just as quietly.

According to Katz, during her son’s addiction to increasingly dangerous drugs, the reactions of adults could be categorized as “enabling behavior,” including family members, friends, local police — and even herself.

There was the police officer who caught Ian smoking in the park and sent him home with a free pass. There was the time Katz waited an extra day to demand a urine sample, giving Ian time to get a clean sample, only to learn much later that if had belonged to the younger sibling of a friend.

Ginger Katz of Courage to Speak Foundation speaks to GHS students about her son’s death at the age of 20 of an overdose of heroin and valium. Credit: Leslie Yager.

Drugs and Violence are Connected

Katz said Ian showed signs of trouble in high school. Senior year, Ian received a Tracker from his biological father as a gift. One night, according to Katz, around 2:00 am, the car exploded in the family driveway. Flames shot up over the house.

“The car was fire bombed by a molotov cocktail. Drugs and violence are connected,” Katz said, adding that the family never learned who had been responsible.

After a Death, Secrets Unearthed

“After his death a lot of his friends would visit me because they wanted to see Ian in my eyes,” said Katz. One boy confided that he had done a lot of drugs before getting straight and that when he didn’t have the money to pay for drugs, his dealers had him do favors, including firebombing cars.

“Ian was in over his head,” Katz concluded.

In college Ian was involved in a violent fight, but instead of being kicked out of school, his biological father pleaded with the dean and Ian was allowed to do community service. Before he completed his hours of service, an adult waved the remainder.

Katz next described how Ian began snorting heroin and became hooked, but that he convinced his biological father to keep it secret from her when he went to a rehab facility several blocks from college.

Ironically, Katz said that at one point, she asked a doctor about Ian’s situation, and was told it was confidential because her son was over 18 and therefore an adult.

Katz said her son moved from marijuana to cocaine in his freshman year in college. “Then, sophomore year… Heroin comes in small packets that can be snorted or smoked. Kids back then thought it was no a big deal,” Katz said. “A boy in his dorm, a heroin addict, gave three boys heroin one night. One got scared. One got sick. Ian got hooked.”

Katz’s approach is not to lecture, but she does share facts. She explained to the GHS students that addiction progresses more quickly among adolescents than adults. For example, a 30-year-old adult takes 8-10 years to reach the chronic stages of alcoholism, whereas an adolescent can take fewer than 15 months because their bodies are still growing. She also mentioned that while Ian’s college tuition was $30,000 a year, the same as a month in rehab.

After Ian’s death, two of his girlfriends said Ian had told them he had been inappropriately touched by a babysitter when he was 10. Katz said that one of the most important part of her program is that every child find 3-5 adults they trust and share secrets with. “Don’t keep your pain inside. Have the courage to speak.”

Katz said that after Ian’s death, she was told the toxicology report on Ian’s death would take some time. “But we knew. Doctors told us to tell people Ian died of an aneurysm or a heart attack and that wasn’t the truth… I had a vision of speaking out. I said if this is happening to us, it’s happening to other families. And I never lied about Ian and wasn’t going to start lying after his death. I was not ashamed of him,” she said, adding that the next day she and Larry buried Ian and began speaking out.

Katz said that after Ian’s death, she was told the toxicology report on Ian’s death would take some time. “But we knew. Doctors told us to tell people Ian died of an aneurysm or a heart attack and that wasn’t the truth… I had a vision of speaking out. I said if this is happening to us, it’s happening to other families. And I never lied about Ian and wasn’t going to start lying after his death. I was not ashamed of him,” she said, adding that the next day she and Larry buried Ian and began speaking out.

More information on Katz’s organization Courage to Speak Foundation is available online.

Related Stories:

- GHS Grad Breaks Silence on Drugs from Marijuana to Heroin

- Heroin: The Elephant in the Room?

- Talk Turns to Heroin in Norwalk

Email news tips to Greenwich Free Press editor [email protected]

Like us on Facebook

Twitter @GWCHFreePress

Subscribe to the daily Greenwich Free Press newsletter.