The evidence is in, and 2021 is proving to be a down year for maple syrup production in Connecticut. The late-winter night/day temperature differences that promote sap flow in a Maple tree have not been large enough – consistently enough – to have a bumper crop.

A normal season lasts 4 to 8 weeks. This year’s season only went about 3 weeks. Yields are down. Significantly.

At Rick’s Sugar Shack, in East Hampton, Connecticut, owner Rick Walker admits “it’s been a terrible year. I normally produce 120 gallons in a season; this year, I’m down to about 70.” At $70 per gallon for Connecticut maple syrup, making that revenue up through Rick’s summer-vegetable sales is going to be difficult.

Blythe Spirits

The funny thing is, no one seems to be complaining.

Spend more than 2 minutes with maple tappers, and you will realize that they are some of the most cheerfully positive people around. Rick Walker is a rather stoic guy, but when he starts explaining the intricacies of sugaring, it becomes apparent that he lives for this part of the year.

Erika Tucker, a hobbyist Maple Tapper who’s also from East Hampton, generously peppers her emails with smile

and maple-leaf emojis when she writes about sugaring. Her passion is real: a trip to the Von Trapp Family Lodge

at Stowe “started an addiction that had us seeking out sugar shacks far and near and eventually tapping our own trees.”

Barbara Fahr administers “CT Maple Tappers,” the most popular Facebook sugaring hobby page in the State. For her, “maple sugaring [is] addicting and consuming.”

Erika’s greater goal is to “have fun, create memories with my family, and teach my children about living from nature

and how rewarding hard work can be.” It’s a Jeffersonian notion: farming as hard work and satisfaction.

Sam Kantrow, Weatherman at Channel 8 in New Haven and Do-It-Yourselfer extraordinaire, dittos Erika: a family hobby. Appreciating nature’s bounty. Teaching the kids about hard work. Kantrow adds: “unlike gardening, sugaring is instantly gratifying; you put in a tap, and the sap flows right away.”

Finally, there’s a somewhat unspoken nerd factor to sugaring. If you didn’t like math or science in school, sugaring may not be for you. Tim Gannon has been running the community sugar house at Parmelee Farm in Killingworth for 7 years. His favorite thing about sugaring was “learning how neat the whole process is, and how much science is involved [in it].” Tim leads a volunteer army from the town, bottling about 50 gallons a year from about 250 taps on the farm and elsewhere in town.

Xylem-Sap Flow

There is perhaps no agricultural crop in the world that is so directly tied to nature’s annual re- awakening than Maple Syrup. Sap begins to flow in a Maple because the ambient temperature changes force the tree’s central, vertical xylem cells to contract and de-contract.

This xylem-sap contains only about 2% sugar. In fact, Tucker, who calls it “sugar-water,” does not believe it is sap at all. That sugar concentration does not offer anything close to the energy needed to power the tree over the entire year, but it is enough sugar to get the tree’s buds to break. The buds, in turn, create leaves that allow the tree to carry out photosynthesis. And as we all know, photosynthesis is what really allows a plant to survive and flourish.

If flowers are a metaphor each Spring for our own renewal, and a harbinger of possibility for the year to come, how much more powerful a symbol is this first step – this seemingly spontaneous genesis due only to variation in temperature?

Is it any wonder that we are so attached to maple sap? Certainly, Maples are beloved of New Englanders because their abundance here makes them “our tree.” Yet is there not also, perhaps, a more powerful, subliminal attachment in our love for the Maple, and its product, Maple Syrup?

This Sugarin’ Life Ain’t Easy

Steve Greenwood has been sugaring for 12 years, with 103 taps on 70 sugar maples. For him, sugaring “brings friends and family together during the short season.” With cheeky irony, he shrugs “[besides] what else is there to do in February and March?

Spoken like a true Yankee. In fact, if you’re not inclined to hard physical work and long hours, there is plenty to do in February and March, most of it having to do with sitting on a couch and watching the basketball tournament.

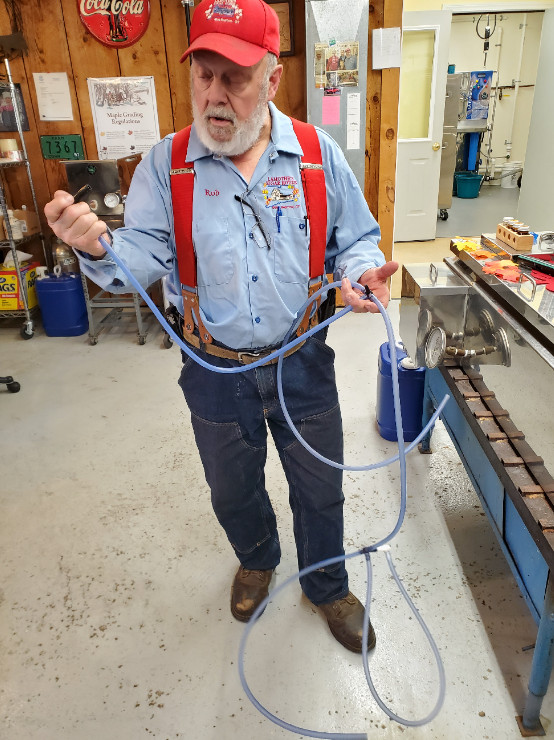

Sugaring has a very low barrier to entry: a few buckets and taps, maybe some tubing, a stove or grill, some wood, and a couple of hotel pans usually do the trick. About mid-March, I visit Kantrow at his home in Madison. Sam gleefully fills me in on a hack: “a cord of wood to heat the evaporator costs about $200-250, but if you get slab wood [leftovers] at a saw mill, it’s half the price!”

The real buy-in comes with the discipline sugaring requires: a lot of physical labor, a very watchful eye, a good feel for numbers, and a meticulous attention to detail, or “the recipe.”

There are several crucial steps. You need to collect the sap on time. It’s considered a venial sin in sugaring to let your buckets overflow, a mortal sin to let them freeze over. So you need to check them every day. Then, because sap contains sugar, a natural substrate for bacteria, you have to boil it immediately to avoid mold – no matter how much you collect. That may have you boiling well into the night, but such is The Tapper’s Burden.

You cannot leave the boil. Especially as it gets to completion. The margins are exceedingly tight: maple syrup will only turn out right when it gets to 218˚ Fahrenheit (7˚ above boiling water) at a specific gravity between 66.9˚ and 68.9˚ on the Brix Scale of dissolved sugar.

Rick Walker tells the tale: “I once went into the other room to check on filtering a previous batch, and came back two minutes later. The boil had gone over 218˚, and all I had was rock candy. I was lucky my pan hadn’t burned; I

would have had to throw it away, and that’s about $300 lost.”

The next step seems unnecessary for those who are content to go with what nature gives them, but is, in fact,

crucial: filtering for Niters. Sardonically called “Sugar Sand” in the industry, gritty niters make the syrup experience extremely unpleasant, and must be taken out. Hobbyists do this with triple coffee filters; commercial facilities do it through fancy ten-plate filtering machines.

And then there’s the check to see how your syrup grades out. Consumers pay a great deal of attention to grades, because… well… they’re grades, for Pete’s sake! Yet grades will only tell you the color of the syrup, and indirectly, how light or heavy it is. In fact, grades are exclusively a function of how much sugar is in the sap: sap collected early in the season contains more sugar, so it does not need to be boiled as long. Therefore, it is less viscous and lighter in color.

The State of Vermont officially recognized consumer frustration on this matter a few years ago (it had been a bone of contention for decades) by changing the qualitative-sounding grade distinctions. Words like “fancy,” and the off putting “commercial grade,” as well as distinctions between “A” and “B” grade syrup, were eliminated.

There are now only 4 grades: Golden, Amber, Dark and Very Dark. Sell your syrup under the wrong grade, however, and the Feds will come after you and fine you quite substantially!

A Golden Age

Since 2010, Maple Syruping has been going through a Golden Age, even if this has also been tempered by a real concern about Climate Change. World production in 2010 was 10.7 million gallons. It is now 18.7 million gallons. That represents a production increase of 75%.

Until the late 1990s, maple syrup production was beholden to the same issues that plague any crop: in boom years, prices fell; in meager years, prices rose, but not enough to scratch out a good living. Québec, the behemoth that produces 13.2 million gallons (70%) of the world’s maple syrup, decided to do something about this.

Québec had formed a collective marketing agency as early as 1966: the Fédération des producteurs acéricoles du Québec (FPAQ), or Federation of Québec Maple Producers. In 2000, the FPAQ became the exclusive sales agent for bulk sales of maple syrup in the Province, and in 2004, they created a quota system with living – but fixed – prices for all producers in Québec, large or small. In essence, the FPAQ became the OPEC of maple syrup.

The rising tide created by the FPAQ floated all sugaring boats – not just the ones in Québec. In fact, because U.S. producers were not tied to the agreement, they got the benefit of higher prices – just like Québec producers – but they did not have to observe the quota restrictions imposed on their northern brethren.

This has created no small amount of controversy in Canada (and a thriving black/grey market there and across the border). But in the U.S., it launched a staggering boom in production. Whereas Québec’s production has increased 65% since 2010, Vermont’s has gone up 149%. Even Connecticut doubled its production in 2011, and has stayed t the same production level since.

As of 2020, Québec is still the undisputed leader in maple syrup production, but its world market share is down from 74.88% in 2010 to 70.7% in 2020. U.S. world market share has risen from 18.35% to 23.42%, and Vermont’s share has gone from 8.34% to 11.89%.

The Syrup River (and Lake)

Where is all this syrup going? Québec operates a strategic reserve of approximately 9 million gallons. Indeed, the strategic reserve is a major reason why prices for syrup can remain high and stable.

But product innovation is maple syrup’s real success story. The market for syrup stood at $780 million in 2018. It is expected to reach about $1.14 billion by 2025.

Maple syrup is viewed as a healthier – and in any case, less refined and more organic – sweetener. For an increasingly vegetarian or vegan part of the population, maple syrup is a better answer than sugar, to say nothing of corn syrup.

A much smaller percentage of maple syrup goes on pancakes and waffles than it used to. Uses today tend more toward salad dressings, mustard, sauces, oatmeal, yoghurt, or roasted vegetables. Cornell’s food science program is developing maple beer, wine, soda, and even kombucha. There are now maple syrup cosmetics and restorative maple syrup sports gels.

In Connecticut, the cost of doing business is higher, so syrup here is just more expensive than elsewhere. A gallon here costs about $70 on average; in Vermont, it’s $35, and in Québec, it’s $30.

And that’s where good ol’ Connecticut Yankee

salesmanship and marketing comes in. Lamothe’s, in Burlington, is the largest sugar house in the State. They were finished sugaring even before Maple Weekend, and their operation is an impressive, computer-controlled testament to their steady growth over the years. Their biggest business is in value-added maple candies, popcorn, party and wedding favors, and packaging their maple syrup in every size you can imagine, including customized jugs.

Rick Walker sells his syrup to supermarkets, and even to Goodspeed Opera House, where he says the context of the playhouse makes people more liberal with their wallets. “I sell a small container to them for $4. They turn it around to customers for $10, and those patrons are happy to pay it.”

The Maple Laboratory

Still, this demand-driven growth would not be possible without some supply-side magic as well. Much of the supply growth is driven by technology, but not just mechanical technology.

Production improvements often start in botanical laboratories and agricultural stations run by States and Universities in the Northeast, like those at the University of Vermont and Cornell.

If a maple tree normally takes 30-40 years to reach maturity (and the 10” diameter required for sustainable tapping) cloning and crossing experiments have created hybrid super-producers that can be tapped in 7 years.

Botany Departments are also creating maple-dedicated forests, containing higher percentages of Sugar and Black Maples than Red Maples, and zero non-Maple trees. (Sugar and Black maples have the highest sugar concentration, but forests typically have about twice as many lower-yield Red maples. Forest management is a potentially huge source of efficiency, when one considers, for example, that Vermont – despite being such a major producer – devotes only 3% of its maple forests to sugaring.

A major step forward was the development of improved vacuum technology for the sap-extracting taps and tubes. Tap-hole sanitation is also important, because it keeps the tree free of disease in general. More importantly, it keeps the tree’s defense mechanisms from sending healing hormones that would scar up the tap-wound, closing off sap-flow.

Climate Change

Yet for every two technological steps forward, the maple syrup industry takes one climate change step back.

Sam Kantrow’s job as a Weatherman makes him very attuned to the climate of maple syrup (what some

fancier hobbyists, like my wine-drinking friends, might call “terroir”). “Connecticut is a dividing line between real cold and not-so-cold. I have friends only about 5-8 miles north of Madison whom I call in the morning, when my taps are already running. Theirs won’t be on until mid-day. And then there’s the geographical holes that just produce better. No one knows why; they just do.”

The production line keeps moving further north. This phenomenon is especially noticeable in the most southerly Maple growth zones, like Virginia, where some areas simply do not produce any more syrup.

Some years, like 2021, are simply not as cold as others; the season is shorter, the sap quality and quantity is lower. In 2020, there was drought. Despite the forest management and technology, winters tend to be warmer, there are fewer trees, and tree health and growth is not as strong as before.

François Steichen founded and owns Frenchy’s Wine Road, a Connecticut company that writes copy and content for the wine, spirits and cider industries.

He is a resident of Old Greenwich with 15 years’ experience in the Wine Industry. François started at Harry’s Wines in Fairfield; worked at Acker, Merrall and Condit, in New York, the oldest wine store in America; and has managed stores in Greenwich.

François holds the WSET Diploma, the gold standard in wine education. At 10 years of age, François took his first – chaperoned – sip of a sparkling wine. Since that moment, the magic of fermentation and spontaneously-produced bubbles has never truly relinquished its hold on his curiosity.