Dawn Fortunato first learned that her son, Charlie, had lead poisoning when he was one.

Dawn Fortunato first learned that her son, Charlie, had lead poisoning when he was one.

Having just turned two in December, Charlie, who has a 6-year-old brother, Aidan, never got used to his visits to the blood draw at Greenwich Hospital.

“It usually takes three people to hold him still for the needle in his arm,” Fortunato said. Her matter-of-fact tone belies the emotion on her face when men in white lab jackets pin her 28-lb toddler in place to draw blood from his arm.

At Greenwich Hospital on Jan. 19, the technician couldn’t recall another child’s blood lead levels being tested for anything other than routine precaution to rule out lead toxicity.

At Greenwich Hospital on Jan. 19, the technician couldn’t recall another child’s blood lead levels being tested for anything other than routine precaution to rule out lead toxicity.

Fortunato lives with extended family in her parents’ house, built in 1941 on Booth Court. Holly Hill Resource Recovery Facility, formerly “the dump,” is adjacent to the north. To the west is the Housing Authority property, Armstrong Court.

The 38-year-old mother said she is often asked how Charlie contracted lead poisoning.

“Dating back to the 1950’s, there have been 15 babies raised in this house. With the exception of one child, my child, none have ever contracted lead toxicity. Why?” she asked. “And why one of my boys and not the other?” she asked, referring to six-year-old Aidan.

Fortunato said her nightmare began in the days following Nov. 18, 2013 when Charlie had just turned one. Following a well-baby visit, the pediatrician’s office called about Charlie’s blood test. “They said they were having a problem with their machine and didn’t think it was giving a correct reading and had me bring him back, along with his brother for a re-test,” Fortunato recalled. When the results arrived the news was grim. “The first reading in the office tested at 19.7 and the second test was sent to the lab, tested 20.0. I was flabbergasted.”

Douglas Serafin, head of the Town of Greenwich Health Department’s laboratory said, a reading of 20 represents 20 micrograms per decileter. He explained that a reading of 5 or less is considered good. He added that, although readings can go into the hundreds, those situations result in emergency room visits. Serafin said that although there are few cases of lead poisoning in town, they do exist, and that of those few cases, illness occurs mostly in children who have ingested lead paint chips. He said that even less frequently, but a possibility, is lead poisoning resulting from drinking water from old plumbing fixtures or from ingested soil. (More Town information on sources of lead poisoning.)

Town of Greenwich fact sheet.

Fortunato said the doctors inquired about Charlie’s normal routine. There were many questions asked about the baby’s contact with the radiator in her Booth Court apartment, but none about the soil in the yard.

Fortunato said the doctors inquired about Charlie’s normal routine. There were many questions asked about the baby’s contact with the radiator in her Booth Court apartment, but none about the soil in the yard.

“Everyone just assumed the source of the poisoning was inside our home,” Fortunato said. “When I asked a Town hygienist about testing the soil in the yard, she suggested I pop a layer of mulch down.”

Abatement, Education, Remediation

The pediatrician set in motion a lengthy and expensive process, and both the Town Health Department and the State became involved.

“The doctor said to give Charlie lots of orange juice, an iron supplement, and as many green vegetables as I could get him to eat. And he would have more regular doctor visits and undergo venipunctures for blood sampling during each visit.”

After the Town’s health hygienist called and reviewed standard protocol, the Town sent a nurse to educate Fortunato and her mother about lead and its effects on children. In the past 50 years, with the emergence of new information about neurological, reproductive, and possible hypertensive toxicity of lead, the CDC has progressively lowered the threshold that triggers alarm in Blood Lead Levels (BLL).

The Town also sent a birth-to-three expert to Ms. Fortunato’s home to conduct an assessment.

The Town also sent a birth-to-three expert to Ms. Fortunato’s home to conduct an assessment.

“We were told to hire an independent company to come out and test every room in the house – even rooms Charlie never entered,” said Fortunato, who lives in a nicely renovated basement apartment of a multi-story house. “Testing included the walls, ceilings, moldings, door jams, all wood and concrete surfaces, windows, radiators, floors, the exterior of the home, the water, and, finally, the soil in the yard outside,” she said.

Fortunato contracted with Boston Lead Company, LLC who did a lead inspection, testing the house in the presence of a Town Health Dept. hygienist. “The hygienist just about stood over her watching her ever move,” Ms. Fortunato said. “A week later we received the results.”

Some areas in our home tested 1.0, which is considered a very low positive. These were in parts of the house Charlie didn’t visit or couldn’t reach as a baby, such as kitchen cabinets and windows, which are high up because it’s the basement,” Fortunato said. “The highest test result was for four radiators upstairs in my parents’ living area, which tested between 4 and 12.8.”

Some areas in our home tested 1.0, which is considered a very low positive. These were in parts of the house Charlie didn’t visit or couldn’t reach as a baby, such as kitchen cabinets and windows, which are high up because it’s the basement,” Fortunato said. “The highest test result was for four radiators upstairs in my parents’ living area, which tested between 4 and 12.8.”

Fortunato complied with all the protocols dictated by the State and Town. She spent $2,000 to have old windows removed, $100 for plywood to board them up, $300 for encapsulating paint and $800 for radiator covers. She also paid $10,000 for new windows.

When the lead abatement company paid their third visit, the Fortunato home was finally declared lead free in a letter dated April 2, 2014.

What nags at Fortunato as she brings Charlie to the hospital’s blood draw center for the fifth time, anticipating her boy’s screams of fear and pain, is the generally dismissive attitude to any questions about lead in the soil in her neighborhood.

According to the CDC, lead contaminated soil can pose a risk through direct ingestion, uptake in vegetable gardens, or tracking into homes. Uncontaminated soil contains lead concentrations less than 50 parts per million (ppm), but soil lead levels in many urban areas exceed 200 ppm.

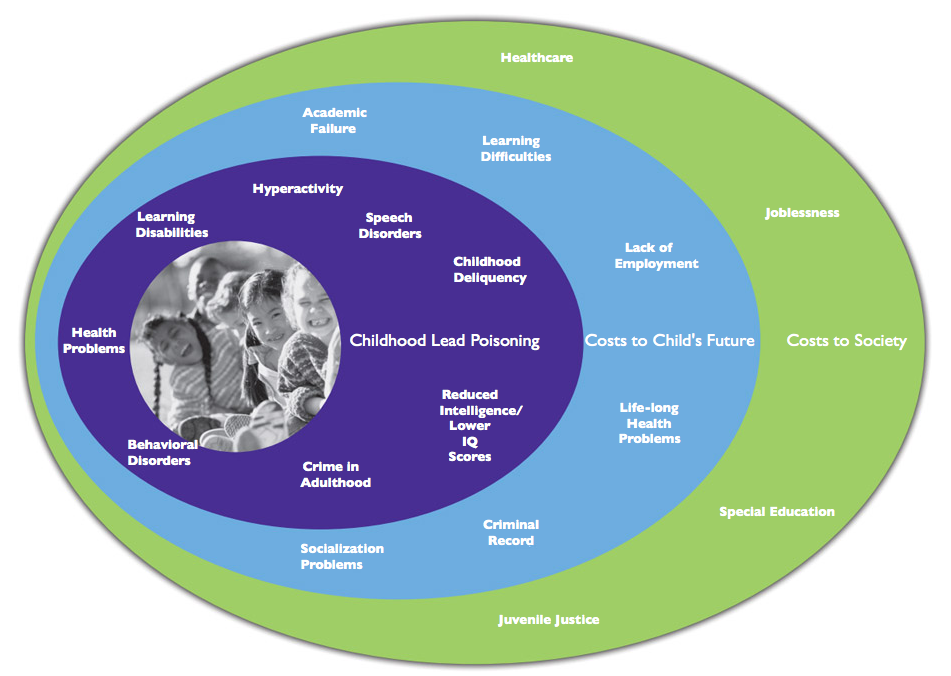

Ripple effects of childhood lead poisoning. Credit, State of Connecticut lead poisoning prevention program.

Serafin, whose department conducts a variety of tests ranging from ticks to radon to lead and blood, said Connecticut has a lead poisoning prevention program. He also said lead was used in paint until 1978.

“Lead gives paint wonderful colorful pigments. The Romans used lead in paint. Metals were often used in paint. That’s why you hear of colors like cobalt blue,” Serafin said, adding that anyone can bring in a sample of a paint chip from their home and, for $51.00, the lab, open from 8:00am until 3:00pm on the ground floor of Town Hall can have the paint tested for lead, with results available in a week.

Fortunato said that results of the State of Connecticut Health Dept.’s soil tests taken in 7 locations in her yard in December 2013, read up to 300 ppm and 353ppm (365104_109_fr) And, next door, at Armstrong Court, Complete Environmental Testing, Inc. (CET) an environmental testing service certified in Connecticut, found in 2011 that soil samples measured 420ppm in the area of Giant Steps and Head Start Preschools.

The EPA’s standard for lead in bare soil in play areas is 400 ppm. This regulation applies to cleanup projects using federal funds.

Fortunato used to bring her children to the playgrounds at Armstrong Court, but has since stopped. “Everyone is so eager to write me off and say it’s just paint chips,” Fortunato said. “But I was promised the Town would test the soil for real and now, all I hear is crickets.”

“When I called into the WGCH radio show, Greenwich Matters, on Dec. 19, hosted by the chair of the Town Housing Authority board, Sam Romeo, he accused me of wanting to stop his improvement projects at Armstrong Court,” Fortunato said.

“When I brought the claim on the housing authority website that the soil in northwest corner of Armstrong Court was “fully clean” – where they had hoped to put in a parking lot a stone’s throw from my house and the former dump – he turned the tables on me,” Fortunato said, in disbelief. “‘Don’t you feel guilty your boy has lead poisoning?’ he asked me!” Fortunato recalled of the Dec. 19 radio show.

“When I said the chain of custody form was missing and I didn’t believe the soil was clean, he accused me of slander,” Fortunato said.

“The thing is, I’m a mother of a sick kid. I don’t want any other child to have to suffer like this. It has been a really long road. Just a nightmare experience. I don’t want any other parent to go through this. That goes for Armstrong Court families, or anyone in Chickahominy. Anyone downwind of the dump, where that incinerator burned for years and local factories dumped waste into pits, thousands of gallons at a time.”

“The thing is, I’m a mother of a sick kid. I don’t want any other child to have to suffer like this. It has been a really long road. Just a nightmare experience. I don’t want any other parent to go through this. That goes for Armstrong Court families, or anyone in Chickahominy. Anyone downwind of the dump, where that incinerator burned for years and local factories dumped waste into pits, thousands of gallons at a time.”

Fortunato said that the First Selectman, Peter Tesei, promised to organize a meeting between the Town and concerned neighbors. “I’m sure he will make good on his promise, but that was in November. I’m asking him to follow through on thorough testing of the soil, but now he hasn’t replied to my two emails on Jan. 12 and Jan 20 trying to arrange a date,” Fortunato said. “I get the ‘read receipts.’ The email has been opened several times,” but no reply.

“I’ve also sent a Freedom of Information Act request to Mr. Romeo for the Chain of Custody report from the soil samplings at Armstrong Court that are missing from the website, but critical to the determination of “clean,'” Ms. Fortunato said, adding that she has received no reply from the chair of the Housing Authority Board.

“I’m waiting for answers,” Fortunato said. “I’ve complied with everything the Town and the State required me to do on my family property, but I cannot get a response from the Town about a thorough testing the adjacent housing authority property.”

“The good news is that after a full year of this nightmare, just today, I got the results of Charlie’s blood test. He’s finally in the clear with a result of a 3,” Fortunato said on Wednesday. “Now let’s find out what’s in the neighborhood soil once and for all.”

More information on lead poisoning from State of Connecticut Health Dept.

Email news tips to Greenwich Free Press editor [email protected]

Like us on Facebook

Twitter @GWCHFreePress