Submitted by Jonathan Kantor

My grandparents spent most of their adult lives living in a quaint split-level home in Fair Lawn, New Jersey. They had funny accents. They were born in a tiny town in Poland that’s hard to pronounce and even harder to spell. But with a giant American flag standing tall at the front of their house, you would never know they weren’t born here.

My grandparents spent most of their adult lives living in a quaint split-level home in Fair Lawn, New Jersey. They had funny accents. They were born in a tiny town in Poland that’s hard to pronounce and even harder to spell. But with a giant American flag standing tall at the front of their house, you would never know they weren’t born here.

Before he passed away in 2019, we used to celebrate my grandfather’s birthday on July 4, even though that wasn’t his birthday. It was a nod to the love and gratitude he felt toward the United States—at least in part—as well as a reminder that we didn’t know what day he was actually born. That information, along with three of his brothers, his parents, most of my grandmother’s family, and countless friends and loved ones, died at the hands of the Nazis.

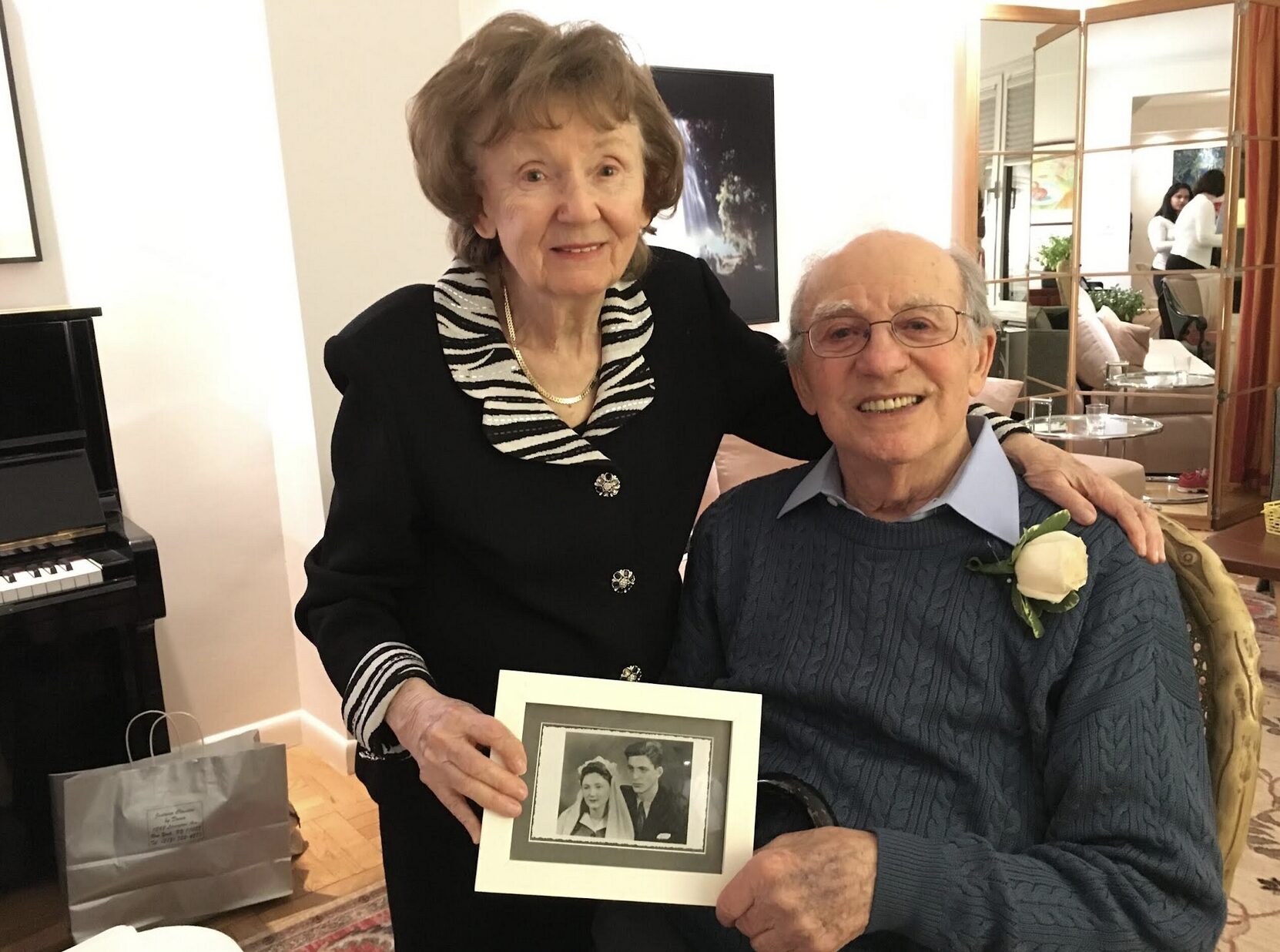

Irving and Sonia Sklaver in 2017, celebrating their 70th wedding anniversary. Photo courtesy Jonathan Kantor

My grandparents’ holocaust survival stories were a fixture of my childhood and the stuff of Hollywood movies. Every time I recount them, my heart swells with pride at their resilience and sheer luck. The stories always end the same way—with an arrival to America, as if that was the moment when their lives could begin. I often imagine how they must have felt passing the Statue of Liberty for the first time, wondering if what they’d heard about the American Dream could happen to them.

While their WWII survival stories seem unfathomable, their American stories represent the fulfillment of the promise that our founding fathers died to protect, achieved by so many hard-working immigrants, generation after generation. That anything is possible in America.

My grandparents didn’t just thrive in America. With the Stars and Stripes waving at their doorstep, they housed and helped countless immigrants from all over Eastern Europe fleeing persecution in search of the American Dream. The people they housed, like them, came speaking no English but relished the opportunity to make it here, working hard to bring their relatives and loved ones so they could make it, too.

My grandparents’ desire to help refugees find their footing in America inspired a family philosophy of sorts: “Tikkun Olam,” which means “to repair the world.”

It’s no coincidence that when my family moved to Greenwich in 1994, their daughter (my mother) got very involved as a board member in an organization called Jewish Family Services (JFS) of Greenwich, whose guiding principle is also “Tikkun Olam.” JFS is a small nonprofit agency that provides critical social services to people of all backgrounds, regardless of race, religion, or beliefs—even cultures that historically fought against the Jews’ very right to exist.

In August of 2021, I watched the news on TV in horror as the Taliban takeover in Afghanistan lead to complete chaos. Desperate Afghan civilians rushed Kabul Airport to flee for their safety. The Taliban immediately began hunting down political adversaries and anyone who had worked with the United States government during their occupation, causing millions of Afghans to flee their homes.

Most Afghan refugees went to Iran and Pakistan, but thanks to Operation Allies Welcome, 76,000 evacuated Afghans made it to the United States. JFS of Greenwich was asked to step up and help to resettle refugees in Connecticut—the first time the organization had done anything like that since the 1990s, when Russian families were resettled from the former Soviet Union.

When the proposal to help Afghan refugees came to the JFS board, the result was unanimous: “Our mission is Tikkun Olam; we must step in to help those in need.”

In December of ’21, the CEO of JFS of Greenwich, Rachel Kornfeld, told me about two young men, aged 18 and 21, who were coming from Afghanistan that had been placed in JFS’ care to help them resettle. The Taliban was after their older brother, and their lives were being threatened. They had no choice but to flee. With thoughts of my grandparents’ legacy, I jumped at the chance to volunteer and help them get settled.

The young men were kind, appreciative, inquisitive, and warm. But what was so apparent in nearly every interaction we had was their desire to be self-sufficient.

Through a translation app, and sometimes through an interpreter, we discussed the importance of attending English lessons, potentially finishing school, and that after 3 months post-arrival, our government expected them to have jobs and be able to afford rent.

I spent a lot of time with “the boys.” We practiced English together. We celebrated birthdays. I helped them secure a small apartment down the street from my home in Old Greenwich. They came over for breakfast and dinner and got to know my family well. I helped the older brother—who was in graduate school for economics back in Kabul—get a job at a pizzeria in Stamford. The younger brother also began working at a different pizzeria nearby. Donated bikes and helmets helped them get to and from their jobs. Ironically, shortly after moving to California in 2022 to be closer to the large Afghan community there, they both got jobs in manufacturing at Tesla.

Their story is like those of millions of refugees who have come to the United States fleeing persecution in search of the American Dream. Refugees are significant contributors to the U.S. economy. A recent study by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services noted that over a 15-year span, refugee groups have contributed “a staggering $123.8 billion more than they have cost in government expenditures.”

HIAS, a federal resettlement agency, found that by the time refugees have been in the U.S. for “20 years, they earn an average of $4,300 more per year than native-born citizens.” HIAS also reported that 13% of refugees in the U.S. start businesses, generating $6.7 billion in business income in 2022 alone.

Since 2021, JFS of Greenwich has helped to resettle thousands of people fleeing dire situations from Afghanistan, Ukraine, Haiti, Venezuela, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and more.

But the slew of Executive Orders over the past month has put a complete halt on reception and placement of refugees and other immigrants to the United States.

Many of those seeking refugee status were already deep into the process of lawfully entering the country and are coming from “the most unstable and desperate places in the world,” according to The New York Times.

With federal funding now frozen, JFS of Greenwich has had to lay off 13 people, just as countless jobs at nonprofits all over the country are being cut. They’re now relying entirely on private funds to assist clients who arrived before the Executive Orders but no longer have government support.

Temporary protected status for Venezuelans has been rescinded, indicating that many will be deported by the end of the year. Haitian humanitarian parole is set to end in August, ending a decades-long, bipartisan effort to help resettle Haitian nationals. Legal services for unaccompanied minors have been issued a Stop Work Order, leaving the most vulnerable children in the country without representation. Imagine your child or grandchild being alone in a foreign country, expected to advocate for themselves, not knowing if they’ll be safe or if you’ll ever see them again.

If my grandparents were alive today, they would be absolutely horrified and devastated at the scorched earth nature of these Executive Orders. There were rumblings that those at risk for deportation were “criminals”, “those who came here illegally,” or “gang members.” The reality is, millions of hard-working individuals who are here legally, pay their taxes, follow the law, and seek to fulfill the American Dream are about to be kicked out.

There’s only one word to describe what’s happening right now: inhumane.

And to those who feel America is better off without them, I would urge you to remember who we are as a nation, and to me, what truly makes America great.

Inscribed at the bottom of the Statue of Liberty that my grandparents and millions of immigrants passed on their journeys to the United States are the indelible words penned by Emma Lazarus:

“Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

We can talk about how we got to this point, but I don’t think that’s helpful. We can easily point fingers, but I’m not going to do that here.

So, what can we do?

Call your elected officials. Write to them. Reach out to organizations like JFS of Greenwich and HIAS and volunteer to help their most vulnerable clients. Write op-eds, share the facts on social media platforms, and speak up.

The America my grandparents knew and loved—our beloved land of liberty and opportunity—is currently on pause. Let’s work together to make our voices heard so it’s not erased forever.

Jonathan Kantor is the grandson of holocaust survivors Irving and Sonia Sklaver. He lives in Old Greenwich with his wife and children and represents district 12 on the RTM.